The Complete Ad Design Guidebook: Mastering Visual Principles for Maximum Impact

Create Ads That Capture Attention, Drive Engagement, and Convert Viewers into Customers

Picture two advertisements side by side. The first is cluttered with information, competing colors, multiple fonts, and no clear focal point. Your eyes dart around the page, unsure where to land, and within seconds you’ve moved on without absorbing the message. The second ad features a striking product image positioned deliberately off-center, complementary colors that guide your eye naturally to a bold call-to-action, and generous white space that lets every element breathe. Before you consciously realize it, you’ve understood the message, felt an emotional response, and remembered the brand. This is the difference between design that happens accidentally and design that happens intentionally.

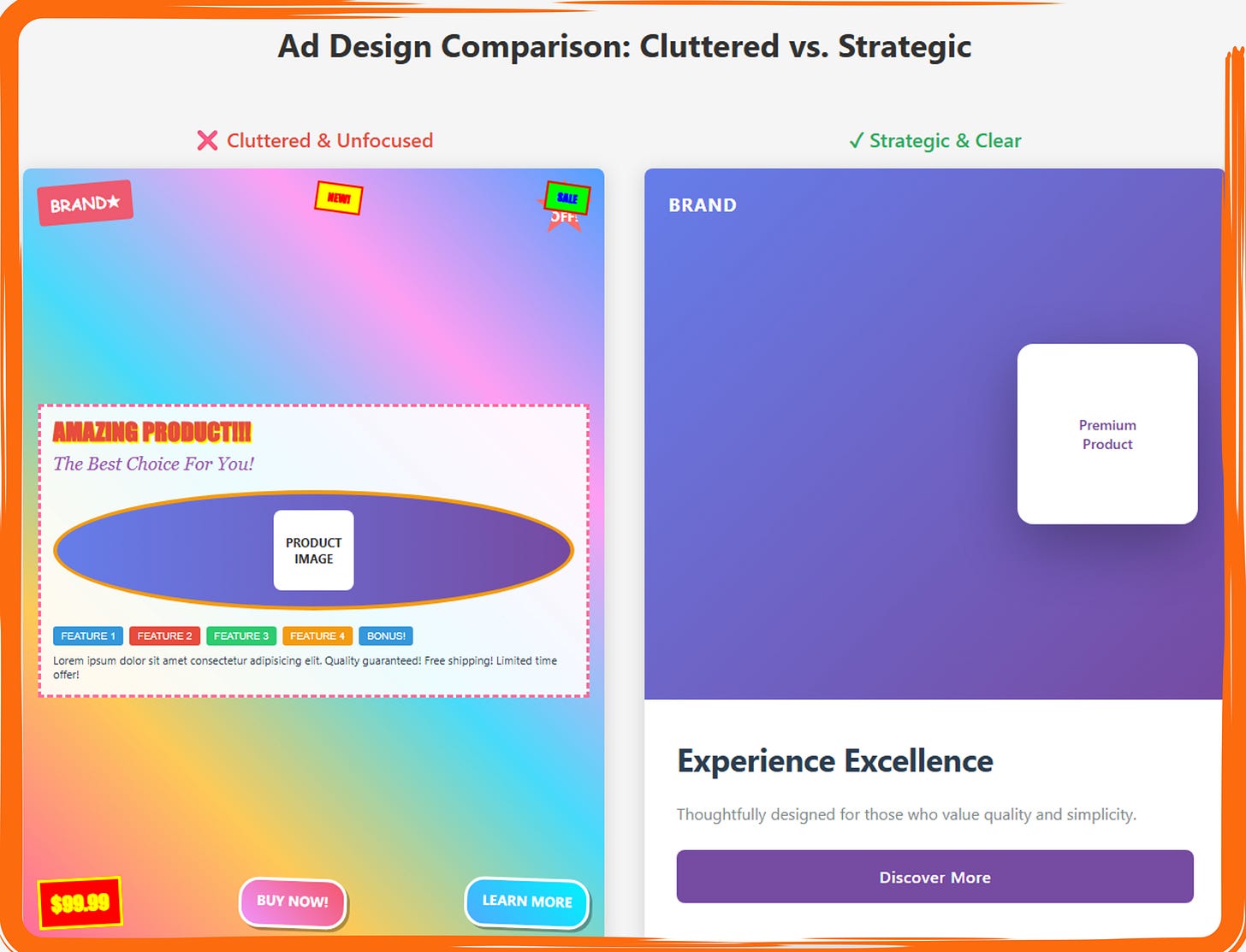

Side-by-side comparison demonstrating the impact of cluttered versus strategic advertising design principles. The left panel (labeled “Cluttered & Unfocused” with red X) exemplifies poor design practices through multiple competing visual elements including scattered brand badges, a busy rainbow gradient background, oversized red headline text (”AMAZING PRODUCT!!!”), decorative bordered content box, five separate colored feature buttons, excessive promotional text, clashing price badge, and two competing call-to-action buttons (”BUY NOW!” and “LEARN MORE”), creating visual chaos where no single element commands attention and the viewer’s eye has no clear path through the content. The right panel (labeled “Strategic & Clear” with green checkmark) demonstrates effective design through minimalist composition featuring a clean purple gradient background, single “BRAND” text in upper left, one prominent product card with “Premium Product” label positioned in the upper right with generous white space, clear headline “Experience Excellence” in large typography, single line of supporting text, and one definitive “Discover More” call-to-action button in branded purple, illustrating how strategic restraint, clear hierarchy, intentional white space usage, and singular focus create professional, effective advertising that guides viewer attention naturally toward the desired action without overwhelming or confusing the audience.

The contrast clearly demonstrates how intentional design principles (golden ratio positioning, 60-30-10 color rule, clear hierarchy, white space) create an ad that communicates instantly and memorably, while the cluttered version creates confusion and cognitive overload.

This visual comparison can serve as a perfect opening for your article or as a teaching tool to immediately show the dramatic difference between following design principles and ignoring them!

Visual principles in advertising aren’t just aesthetic considerations. They’re psychological tools that determine whether your message gets ignored or remembered, whether viewers scroll past or stop to engage, and ultimately whether your ad converts browsers into customers. In an attention economy where the average person sees thousands of ads daily, the difference between effective and ineffective design can mean the difference between a successful campaign and wasted budget. Every color choice, every spacing decision, every ratio you employ either works with human psychology or fights against it.

This comprehensive guide will take you through the mathematical ratios, composition rules, and psychological principles that separate amateur design from professional advertising. You’ll learn how the golden ratio can create naturally pleasing layouts, how the 60-30-10 color rule can make your designs cohesive without being boring, and how simple grid systems can transform chaotic compositions into clear, compelling messages. More importantly, you’ll understand not just what these rules are, but when to apply them, how they work together, and even when breaking them might serve your purposes better.

Think of these principles as tools in a designer’s toolkit rather than rigid restrictions. A carpenter doesn’t use a hammer for every job, and a designer shouldn’t apply every rule to every project. The key is understanding what each tool does, recognizing which situations call for which principles, and developing the intuition to combine them effectively. By the end of this guide, you’ll have a comprehensive understanding of the visual language that makes great advertising work, along with practical methods for applying these principles to your own projects. Whether you’re designing social media ads, print campaigns, or digital banners, these foundational concepts will elevate your work from good to exceptional.

Part 1: Foundation - Understanding Visual Hierarchy

The Psychology of How People Scan Ads

Human beings don’t read advertisements the way they read books, moving methodically from top to bottom and left to right. Instead, our eyes follow predictable patterns shaped by millions of years of evolution and decades of reading habits. Understanding these patterns is the foundation of effective ad design because it allows you to position your most important elements exactly where viewers will naturally look. Eye-tracking studies have revealed that people scan content in distinctive patterns depending on the type of content they’re viewing, and these patterns remain remarkably consistent across cultures and demographics.

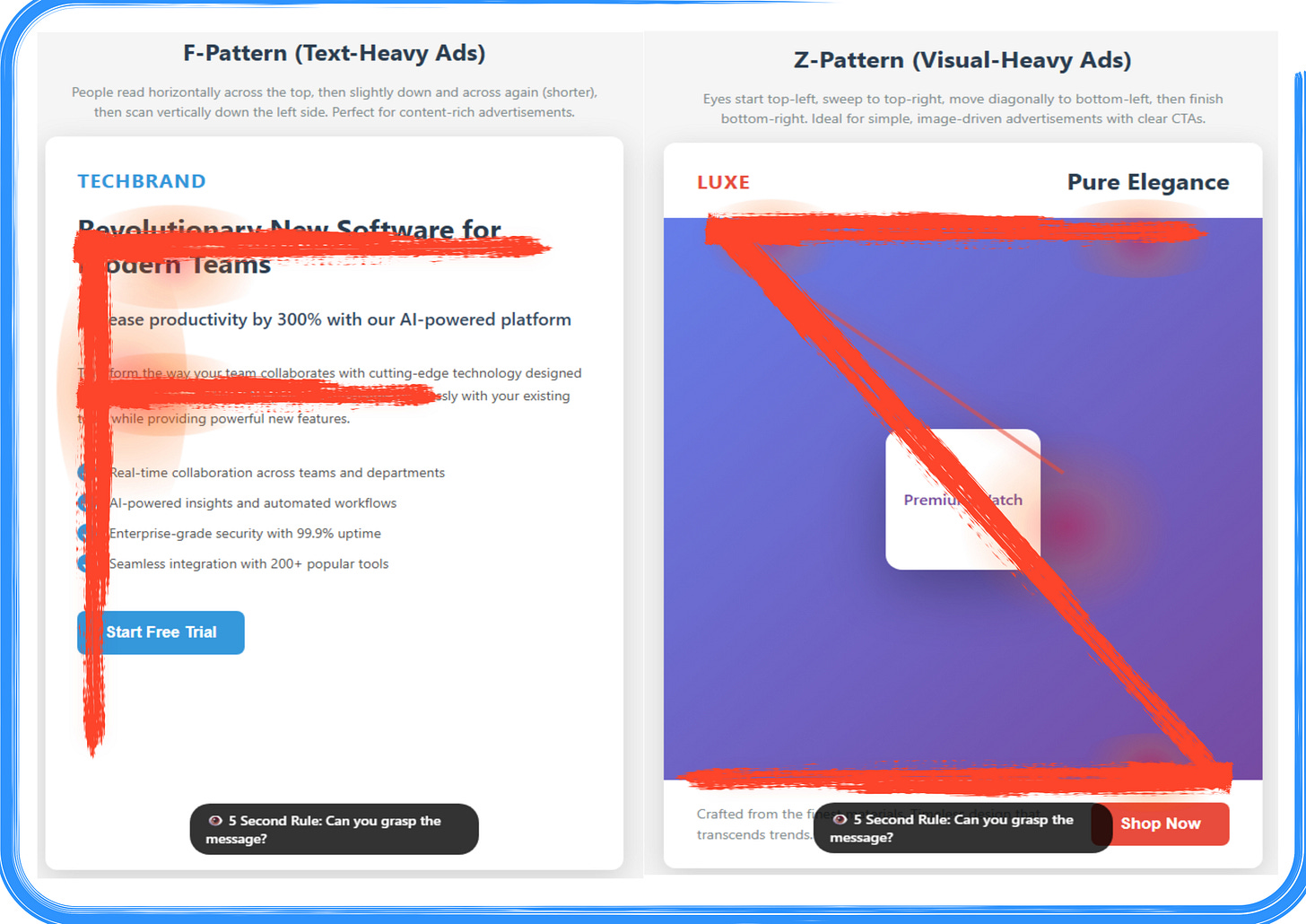

The F-Pattern emerges when people encounter text-heavy content, whether it’s a webpage, a newspaper ad, or a content-rich advertisement. Viewers typically read across the top of the content in a horizontal line, then move down the page slightly and read across in a second, shorter horizontal line, before finally scanning down the left side of the content in a vertical line. This creates a shape that resembles the letter F. For advertisers, this means your headline at the top gets attention, as does the beginning of your first few lines of body copy, but elements positioned on the right side of text-heavy ads may receive significantly less attention. Smart designers place their brand logo, headline, and opening value proposition in the horizontal bars of the F, ensuring maximum visibility.

The Z-Pattern, also called the Gutenberg Diagram, applies to designs with less text and more visual hierarchy. Viewers enter at the top-left corner, which eye-tracking researchers call the “primary optical area.” Their gaze then sweeps across to the top-right corner (the “strong fallow area”), descends diagonally to the bottom-left (the “weak fallow area”), and finishes at the bottom-right corner (the “terminal area”). This pattern explains why so many effective ads place their logo in the top-left, a hero image or headline in the top-right, supporting information in the bottom-left, and their call-to-action button in the bottom-right. The Z-pattern works particularly well for simple, visually-driven advertisements where you want to guide viewers through a story or sequence.

The 5-Second Rule recognizes that viewers won’t study your ad like a fine painting in a museum. In most contexts, you have approximately five seconds to communicate your core message before someone scrolls past, turns the page, or shifts their attention elsewhere. This doesn’t mean your ad should be simplistic or boring, but it does mean that your primary message should be graspable almost instantly. Test your designs by showing them to someone unfamiliar with the project for exactly five seconds, then asking them what they remember. If they can’t articulate your main message, your visual hierarchy needs work. The 5-second rule forces designers to prioritize ruthlessly, eliminating unnecessary elements and strengthening the visual prominence of essential ones.

Comparison of eye-tracking patterns for text-heavy versus visual-heavy advertising designs, illustrated with red overlay paths indicating viewer gaze movement. The left panel demonstrates the F-Pattern reading behavior for text-heavy advertisements, showing a TechBrand software ad with the eye-tracking path (red overlay) starting at the top-left brand name, moving horizontally across the headline “Revolutionary New Software for Modern Teams,” dropping slightly down to scan horizontally across the subheadline about “300% productivity,” then scanning vertically down the left margin through the bulleted feature list, and terminating at the “Start Free Trial” call-to-action button, creating an F-shaped pattern optimal for content-rich advertisements where viewers seek detailed information. The right panel illustrates the Z-Pattern viewing behavior for visual-heavy advertisements, showing a LUXE brand luxury product ad with the eye-tracking path (red overlay) beginning at the top-left “LUXE” logo, sweeping horizontally across to “Pure Elegance” in the top-right corner, then moving diagonally downward across the purple gradient background to the centered “Premium Watch” product card, and finishing with a horizontal sweep along the bottom from the descriptive text to the red “Shop Now” button in the bottom-right, forming a Z-shaped pattern ideal for simple, image-driven advertisements with minimal text and clear visual hierarchy that guides viewers efficiently to the call-to-action.

The 3-Element Rule: Why Less Is More in Advertising

Cognitive psychology research consistently demonstrates that human working memory can comfortably hold about three to four chunks of information at once. When designers try to cram more than three main visual elements into an advertisement, they inadvertently create cognitive overload that reduces comprehension and recall. The 3-Element Rule isn’t about having only three total items in your design, but rather about having three primary focal points that carry your message. Think of these as the headline, the hero image, and the call-to-action, or the product, the benefit statement, and the brand logo. Everything else should be clearly subordinate to these main players.

The power of limitation reveals itself when you examine the world’s most memorable advertisements. Apple’s product launch ads typically feature just the device itself, a short tagline, and the Apple logo. Nike ads might show an athlete, an inspiring phrase, and the swoosh. These brands understand that every additional element you add to a design doesn’t just take up space, it divides attention. If viewers are looking at five or six different competing elements, each one receives only a fraction of the mental processing power. By limiting yourself to three primary elements, you ensure each one gets the attention it deserves and your overall message becomes stronger and more memorable.

Implementing the 3-Element Rule requires discipline during the design process. Start by listing everything you think needs to be in your ad, then ruthlessly prioritize until you’ve identified the three things that absolutely must be there. Often, what seems essential at first glance can actually be communicated through subtext, visual metaphor, or omitted entirely without weakening the message. If stakeholders insist on including additional elements, find ways to group them into visual units that read as a single element, or reduce their visual weight through size, color, and positioning so they clearly become supporting players rather than competing for primary attention.

The 3-Element Rule also creates breathing room in your designs. When you commit to three main focal points, you naturally create more white space around each element, which paradoxically makes each one more noticeable and the overall composition more sophisticated. Luxury brands have long understood this principle, which is why high-end fashion and automotive ads often look sparse compared to retail sale advertisements. The restraint communicates confidence and quality, while the visual clarity ensures the message lands with impact.

This infographic illustrates the 3-Element Rule in ad design by comparing cognitive overload versus focused visual hierarchy. The left panel demonstrates how advertisements with 12+ competing elements (numbered 1-12 in red) fragment viewer attention, resulting in each component receiving only 8-12% of focus—causing the core message to become lost in visual clutter. In contrast, the right panel showcases a streamlined design with just three primary focal points (numbered 1-3 in green): the logo, premium product, and tagline. This minimalist approach allocates 33% of viewer attention to each element, creating a clear visual hierarchy that enhances memorability and impact. The comparison reveals how human working memory’s limitation of holding 3-4 chunks of information directly translates to effective ad design—demonstrating that strategic restraint and generous white space produce more sophisticated, memorable, and persuasive advertisements than busy, element-heavy layouts.

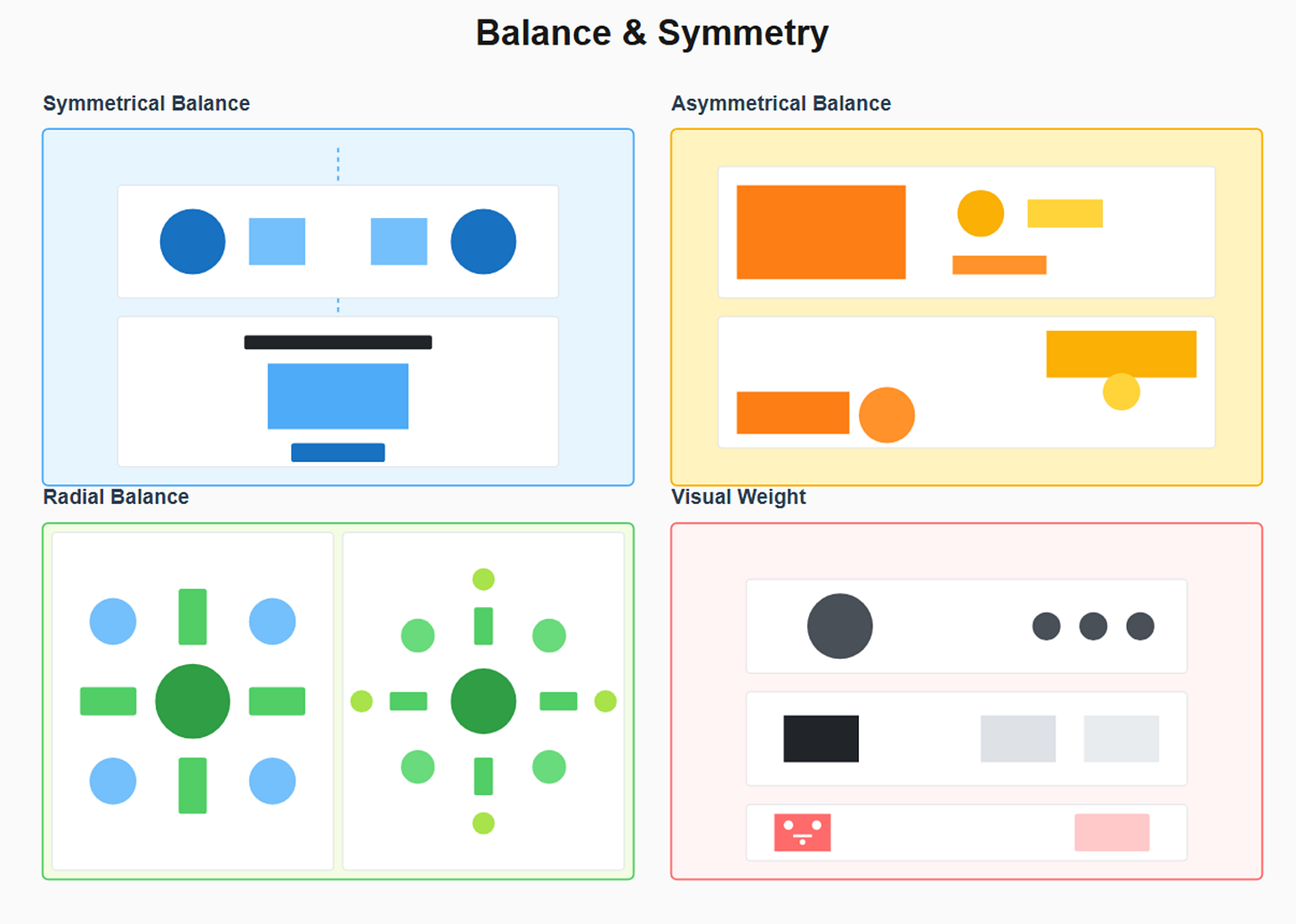

Visual Weight and Controlling Viewer Attention

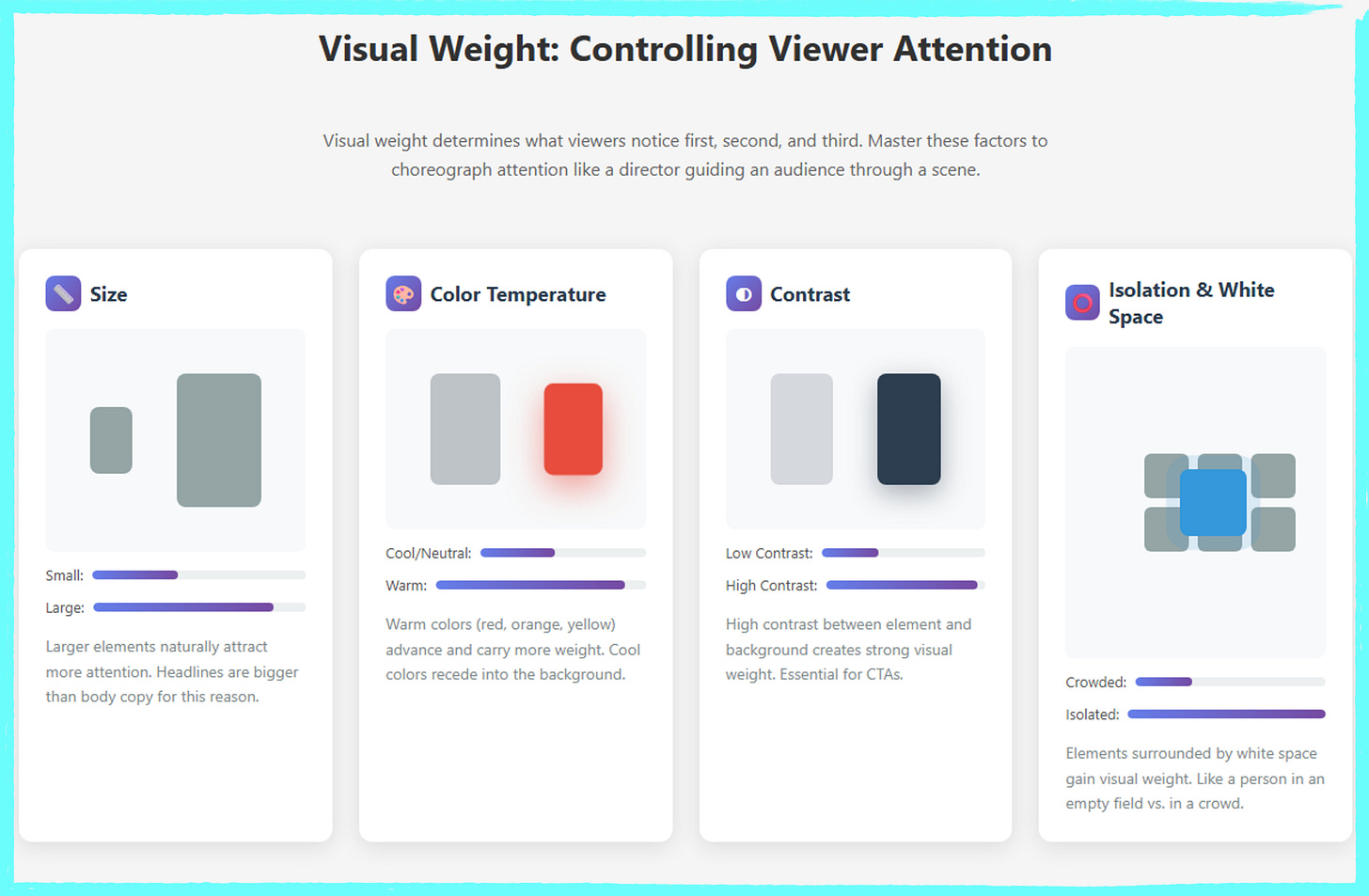

Visual weight refers to how much an element appears to “weigh” in a composition, which determines how much attention it attracts. Elements with greater visual weight pull the viewer’s eye more strongly, while lighter elements recede into the background. Understanding visual weight gives designers precise control over what viewers notice first, second, and third, allowing you to choreograph the viewing experience like a director guiding an audience’s attention across a scene. This isn’t manipulation in a negative sense, it’s communication strategy that respects the viewer’s cognitive resources by presenting information in order of importance.

Size is the most obvious contributor to visual weight. Larger elements naturally attract more attention than smaller ones, which is why headlines are bigger than body copy and why your call-to-action button should be prominently sized. However, size alone doesn’t determine weight. A small element in a bright, contrasting color can easily outweigh a larger element in a neutral tone. Similarly, a small area of high detail and texture will draw the eye more than a large area of flat color. This interplay of factors gives designers multiple tools for controlling attention without making everything important comically large.

Color and contrast dramatically affect visual weight. Warm colors like red, orange, and yellow advance toward the viewer and carry more weight than cool colors like blue and green, which recede. High-contrast elements, where there’s a strong difference between the element and its background, carry more weight than low-contrast elements. This is why call-to-action buttons typically use bright, contrasting colors, they need maximum visual weight to draw the eye and prompt action. Black and white imagery can actually carry more weight than full color in certain contexts because the high contrast makes it stand out against typical colorful surroundings.

Position and isolation also contribute to visual weight. Elements positioned in the optical center of a design (slightly above the mathematical center) naturally draw attention. Elements surrounded by white space gain visual weight because the isolation makes them stand out, much like a single person standing in an empty field is more noticeable than someone in a crowd. Designers can manipulate visual weight to create balance in their compositions, using a large, light-colored element on one side to balance a small, dark, highly-contrasting element on the other side. Mastering visual weight means you can guide viewers through your message in exactly the sequence you intend, ensuring they see your value proposition before your disclaimer, and your product before your footer information.

This infographic breaks down the four fundamental factors that determine visual weight in ad design and their practical application. The top section presents individual weight factors through visual demonstrations and measurement scales: Size (larger elements command up to 85% more attention than smaller ones), Color Temperature (warm colors like red advance and carry 90% weight versus neutral tones), Contrast (high contrast elements achieve 95% weight by standing out sharply from backgrounds), and Isolation & White Space (isolated elements surrounded by white space gain 100% weight compared to crowded elements at 30%). The bottom comparison synthesizes these principles, contrasting a poorly weighted ad with ambiguous hierarchy against a strategically designed version where calculated application of size, warm color, high contrast, and isolation creates numbered visual priorities (1-2-3) that choreograph viewer attention like a director guiding an audience through a scene.

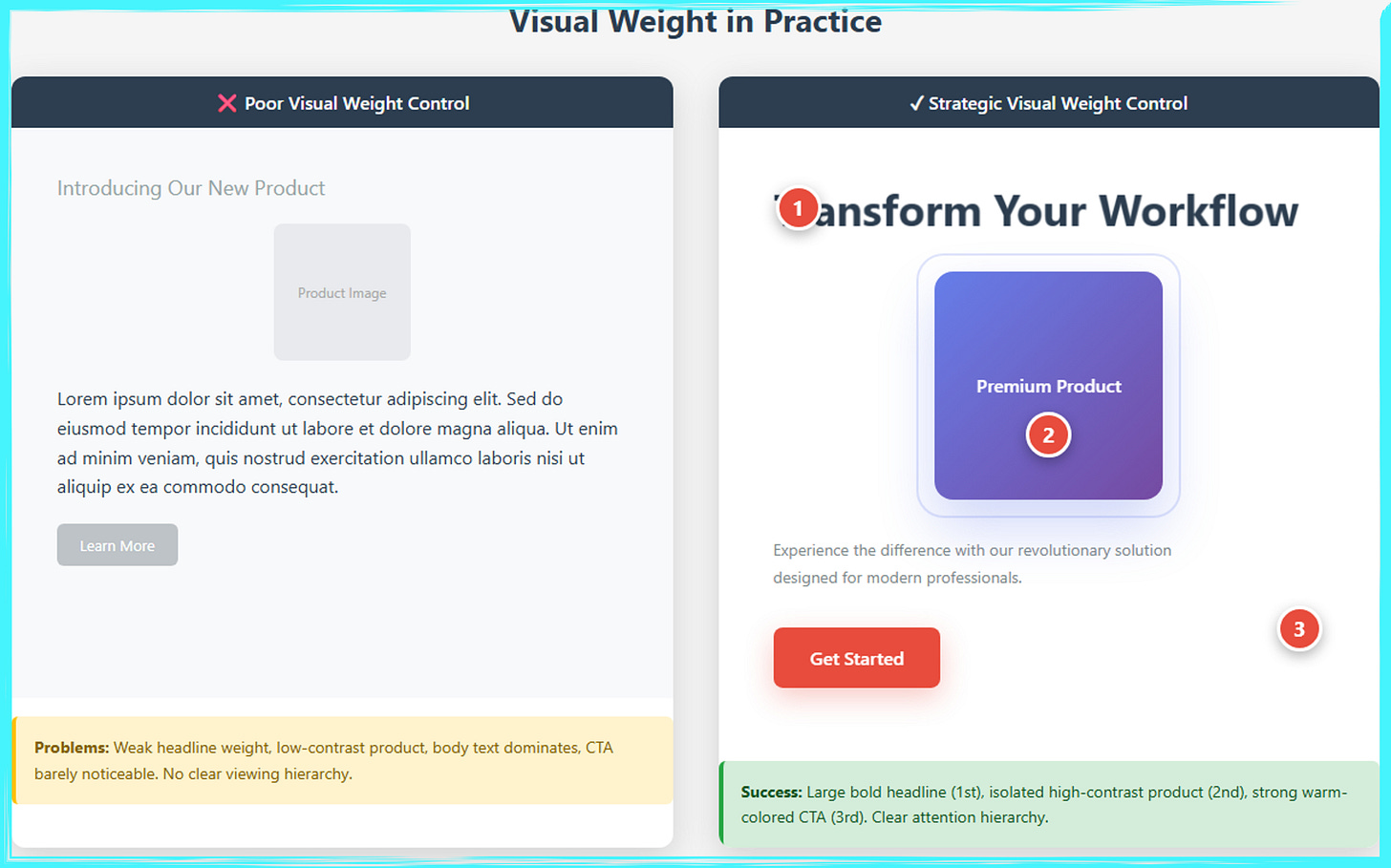

This side-by-side comparison demonstrates the critical impact of visual weight control on ad effectiveness. The left panel illustrates poor visual weight distribution, where a weak, low-contrast headline competes with dense body text, a faint product image, and an inconspicuous call-to-action button, resulting in no clear attention hierarchy and viewer confusion. The right panel showcases strategic visual weight control through three numbered focal points: a bold, large headline “Transform Your Workflow” (1st), a high-contrast, isolated premium product with generous white space (2nd), and a prominent warm-colored CTA button (3rd). This deliberate hierarchy guides viewers through the intended sequence using size differentiation, color contrast, spatial isolation, and restrained body copy, creating a clear path from awareness to action that significantly improves engagement and conversion rates.

White Space as a Design Element

White space, also called negative space, is not wasted space or empty space that needs filling. It’s an active design element that gives other elements room to breathe, creates visual relationships between elements, and paradoxically makes designs look more premium and trustworthy. Novice designers often fear white space, feeling compelled to fill every available pixel with content, imagery, or decorative elements. Professional designers understand that strategic emptiness is often more powerful than additional content, creating focus, clarity, and sophistication that busy designs can never achieve.

White space functions at two levels: micro and macro. Micro white space includes the small gaps between letters (kerning), the space between lines of text (leading), and the padding around buttons and elements. Getting micro white space right ensures readability and prevents designs from feeling cramped or claustrophobic. Macro white space refers to the larger empty areas in your composition, the margins around your ad, the space between major sections, and the breathing room around hero images or primary headlines. Macro white space creates the overall sense of spaciousness or density in a design and establishes the visual rhythm that guides viewers through your content.

Different industries and brands use white space strategically to communicate specific qualities. Luxury brands employ generous white space to communicate exclusivity, sophistication, and confidence. When Chanel or Rolex run advertisements with large swaths of emptiness surrounding a product image and minimal text, they’re leveraging white space to say “we’re so confident in our product’s value that we don’t need to explain or justify it.” Conversely, retail sale ads often minimize white space, packing in multiple products, prices, and promotional callouts to communicate abundance, value, and urgency. Neither approach is inherently better, the right amount of white space depends on your message and brand positioning.

Learning to use white space effectively requires a shift in thinking. Instead of asking “what else can we add here,” start asking “what can we remove without weakening the message.” Look at the empty areas in your composition not as voids waiting to be filled, but as shapes and forms in their own right. In Japanese aesthetics, the concept of “ma” refers to the intentional use of emptiness and space, recognizing that the space between objects is as important as the objects themselves. When you view white space through this lens, you begin to see it as an active participant in your design that shapes meaning, creates emphasis, and delivers a superior viewing experience. Your designs will instantly look more professional, your messages will become clearer, and viewers will spend more time engaging with your content because it’s visually comfortable rather than overwhelming.

This infographic distinguishes between two essential types of white space in design and demonstrates their complementary roles in creating effective advertisements. The left panel explains micro white space—the small gaps controlling letter spacing, line height, and padding around elements—through a direct comparison showing cramped text with poor readability (marked with a red X) versus properly spaced text with generous line height that ensures comfortable reading (marked with a green checkmark). The right panel illustrates macro white space—the large empty areas including margins, section spacing, and breathing room—by contrasting a cluttered grid of nine tightly packed elements that create visual chaos (red X) against a single isolated element surrounded by ample white space that commands attention and creates sophistication (green checkmark). The bottom insight emphasizes that micro white space ensures readability and prevents claustrophobia at the detail level, while macro white space establishes overall spaciousness and visual rhythm at the compositional level, with both types working synergistically to produce professional, comfortable, and impactful designs that leverage strategic emptiness as a powerful design tool rather than wasted space.

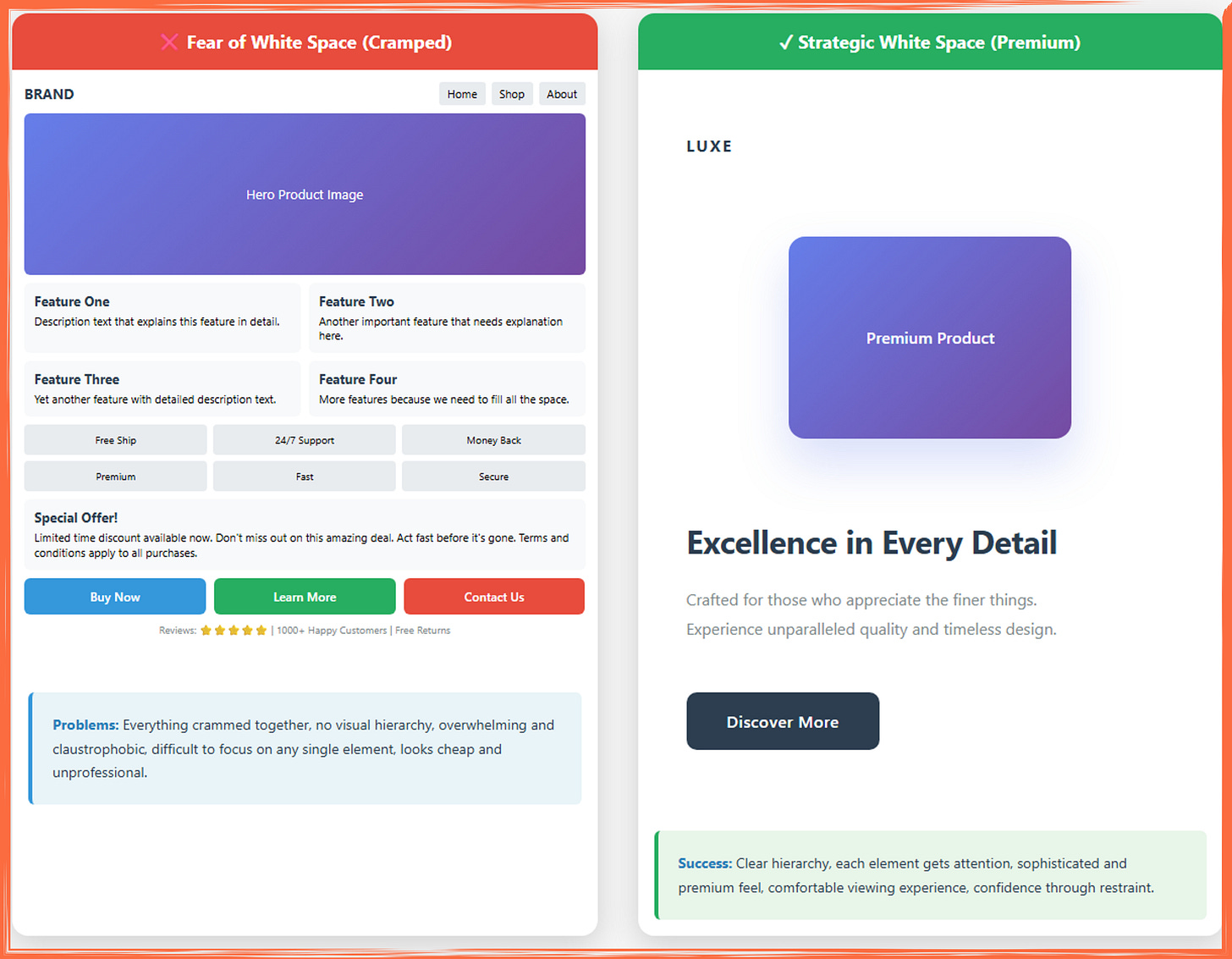

This side-by-side comparison illustrates the dramatic difference between cramped design and strategic use of white space in advertisement layouts. The left panel demonstrates “fear of white space,” where every available pixel is filled with content: a large hero image is immediately followed by four feature descriptions in a tight grid, six benefit badges crammed together, a promotional block, three competing call-to-action buttons, and social proof elements—all packed without breathing room, creating visual chaos, no clear hierarchy, and an overwhelming, claustrophobic experience that appears cheap and unprofessional. The right panel showcases strategic white space usage with the premium brand “LUXE,” featuring generous margins, a single centered product image with ample surrounding space, a bold headline “Excellence in Every Detail” with substantial padding, minimal supporting copy, and one prominent call-to-action button, demonstrating how restraint and intentional emptiness create sophistication, guide attention naturally, project premium quality, and provide a comfortable, confident viewing experience. The bottom annotations emphasize that cramped designs force users to work harder to process information and undermine credibility, while strategic white space establishes clear visual hierarchy, allows each element its moment of attention, and communicates brand confidence through compositional restraint.

This comparison infographic demonstrates how varying amounts of white space communicate distinct brand positioning strategies and target different market segments. The left panel exemplifies a retail/value-oriented approach with minimal white space, featuring a prominent red “MEGA SALE!” banner, dense product grid displaying six items with prices ranging from $19.99 to $44.99, minimal margins between elements, and an emphasis on abundance and urgency—a design strategy that signals accessibility, value, and immediate action to price-conscious consumers seeking deals and variety. The right panel showcases a luxury positioning through maximal white space, presenting a stark black background with a single centered white circle containing “Timepiece,” the minimalist brand name “HAUTE” in elegant letterforms, and vast empty areas dominating approximately 85% of the composition—communicating exclusivity, confidence, premium quality, and refined taste to affluent consumers who associate restraint with sophistication. The bottom insight emphasizes that neither approach is inherently superior; retail brands intentionally minimize white space to convey abundance and competitive pricing, while luxury brands deliberately maximize it to project exclusivity and prestige, making the strategic choice of white space density a powerful tool for brand positioning that should align with target audience expectations, price points, and brand values rather than stemming from design uncertainty or fear of emptiness.

Part 2: Mathematical Ratios for Harmonious Design

The Golden Ratio (1.618:1)

The golden ratio, approximately 1.618 to 1, represents one of mathematics’ most fascinating phenomena, a proportion that appears throughout nature, art, and architecture across cultures and centuries. Also known as phi (φ) or the divine proportion, this ratio describes a relationship where the whole is to the larger part as the larger part is to the smaller part. While this sounds abstract, its visual manifestation is immediately recognizable and deeply pleasing to human perception. From the spiral of a nautilus shell to the proportions of the Parthenon, from the arrangement of flower petals to the compositions of Renaissance paintings, the golden ratio creates a sense of natural balance that resonates with viewers on an almost subconscious level.

The reason the golden ratio feels so naturally right stems from both evolutionary psychology and our daily experience of the natural world. Our brains have evolved to recognize patterns, and the golden ratio is one of the most prevalent patterns in organic forms. When we encounter this proportion in designed objects, it triggers a subtle recognition of natural order and harmony. This doesn’t mean viewers consciously think “ah, the golden ratio” when they see a well-proportioned ad, but rather that the composition feels balanced, professional, and aesthetically pleasing in a way they might struggle to articulate. This subliminal appeal makes the golden ratio a powerful tool for designers who want their work to feel polished and sophisticated.

Practical application of the golden ratio in ad design can take several forms. The simplest is using it to determine the proportions of your layout itself. If you’re designing a rectangular ad, making the width to height ratio 1.618:1 creates an inherently pleasing format. Within that format, you can divide the space using golden ratio proportions to determine where to place primary elements. For instance, positioning your hero image so it occupies approximately 61.8% of the width, with text and white space taking the remaining 38.2%, creates natural balance. You can also use the ratio to determine the relative sizes of elements, making your headline 1.618 times larger than your subheadline, which is in turn 1.618 times larger than your body copy.

The golden spiral, derived from the golden ratio, offers another powerful compositional tool. This logarithmic spiral grows by a factor of the golden ratio for every quarter turn it makes, creating a curved path that can guide viewer attention through your design. Many iconic photographs and advertisements position key elements along this spiral or at its center point, creating dynamic compositions that feel naturally balanced while avoiding static symmetry. Software tools can overlay golden spiral guides on your canvas, making it easy to position your product, model’s face, or call-to-action button at the spiral’s focal point. However, it’s crucial to remember that the golden ratio is a tool, not a requirement. Not every successful ad uses it, and forcing it into inappropriate contexts can create more problems than it solves. Use it when it naturally supports your composition, not as a rigid formula that constrains your creativity.

This comprehensive infographic educates designers on the golden ratio (φ = 1.618) and its practical application in advertisement design. The header introduces the divine proportion as a mathematically derived relationship found throughout nature, art, and architecture that creates inherently pleasing, harmonious compositions. The top section presents four real-world examples nautilus shell spirals that grow by φ with each rotation, flower petal arrangements following golden ratio patterns for optimal packing, the Parthenon’s architectural dimensions reflecting these proportions, and Renaissance masters’ use of φ for balanced compositions accompanied by the mathematical formula demonstrating the relationship. The middle section provides two fundamental visualizations: the Golden Rectangle showing width-to-height ratio of 1.618:1 with clear dimension labels, and the Golden Division demonstrating how to split space into 61.8% (major) and 38.2% (minor) sections for natural balance. Advanced concepts include the Golden Spiral with animated SVG drawing showing how positioning key elements at the spiral’s focal point creates dynamic balance, plus a practical Typography Scale demonstrating harmonious font sizing (42px headline ÷ 1.618 = 26px subhead ÷ 1.618 = 16px body copy). The bottom Golden Ratio in Practice section features an interactive full advertisement layout in 1.618:1 format with toggle-able guide overlays, showing a premium product occupying 61.8% of width (major section) and “Experience Excellence” text in the 38.2% section (minor section), with a practical applications note emphasizing that while the golden ratio naturally supports pleasing composition, designers shouldn’t force it where other proportions better serve their specific needs making φ a powerful compositional tool rather than a rigid requirement.

The Fibonacci Sequence

The Fibonacci sequence represents one of mathematics’ most elegant patterns: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, and so on, where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. What makes this sequence particularly relevant to designers is its intimate relationship with the golden ratio. As the Fibonacci sequence progresses, the ratio between consecutive numbers approaches 1.618, meaning that 8/5 equals 1.6, 13/8 equals 1.625, 21/13 equals 1.615, and so on. This mathematical connection means that using Fibonacci numbers for sizing and spacing creates the same harmonious proportions as the golden ratio, but with the advantage of working with whole numbers rather than decimals.

For typography, the Fibonacci sequence offers an elegant system for creating hierarchical relationships between different text elements. If you set your body copy at 13 points, your subheadings could be 21 points, and your main headline could be 34 points. These aren’t arbitrary jumps, they’re proportional relationships that create visual harmony while ensuring clear differentiation between hierarchy levels. This approach works across any scale, whether you’re designing a business card or a billboard. You might use 8, 13, 21 for smaller formats or 21, 34, 55 for larger ones. The key is maintaining the proportional relationships, which creates consistency and rhythm throughout your design.

The Fibonacci sequence also works beautifully for layout grids and spacing systems. You might divide your canvas into Fibonacci-based columns, such as 5 columns for secondary information and 8 columns for your primary content area, creating a natural 5:8 ratio that approaches the golden proportion. Margin and padding can follow Fibonacci numbers as well, using 8 pixels for tight spacing between related elements, 13 pixels for medium separation, 21 pixels for clear distinction between sections, and 34 pixels for major divisions. This creates a rhythmic consistency throughout your design where spacing never feels arbitrary, and relationships between elements feel intentional and professional.

One practical advantage of the Fibonacci approach over strict golden ratio calculations is simplicity in execution. Designers can memorize the sequence (at least the numbers commonly used in design: 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89) and apply them quickly without calculators or complex measurements. This makes the system particularly useful in fast-paced design environments or when creating design systems that other team members need to understand and apply consistently. However, like all mathematical guides, the Fibonacci sequence should inform your decisions rather than dictate them. If your brand uses a specific font size for accessibility reasons, or if your platform has technical constraints, adapt the system to fit reality rather than sacrificing usability for mathematical purity.

This interactive demonstration reveals how the Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89...) provides designers with an elegant mathematical framework that combines the harmony of the golden ratio with the simplicity of whole numbers. As the sequence progresses, ratios between consecutive numbers converge toward φ (1.618): 8÷5 = 1.600, 13÷8 = 1.625, 21÷13 = 1.615, eventually reaching 89÷55 = 1.618. The visualization shows practical applications across typography (using scales like 13pt, 21pt, 34pt for body, subhead, and headline), spacing systems (8px for tight spacing, 13px medium, 21px section breaks, 34px major divisions), and grid layouts (8:5 column ratios approximating golden proportions). The key advantage is memorability and speed—designers can quickly apply 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 without calculators, making it perfect for fast-paced environments and team consistency. However, these Fibonacci numbers should inform rather than dictate decisions; always adapt the system when accessibility requirements (like minimum 16px body text) or platform constraints demand it, prioritizing usability over mathematical purity.

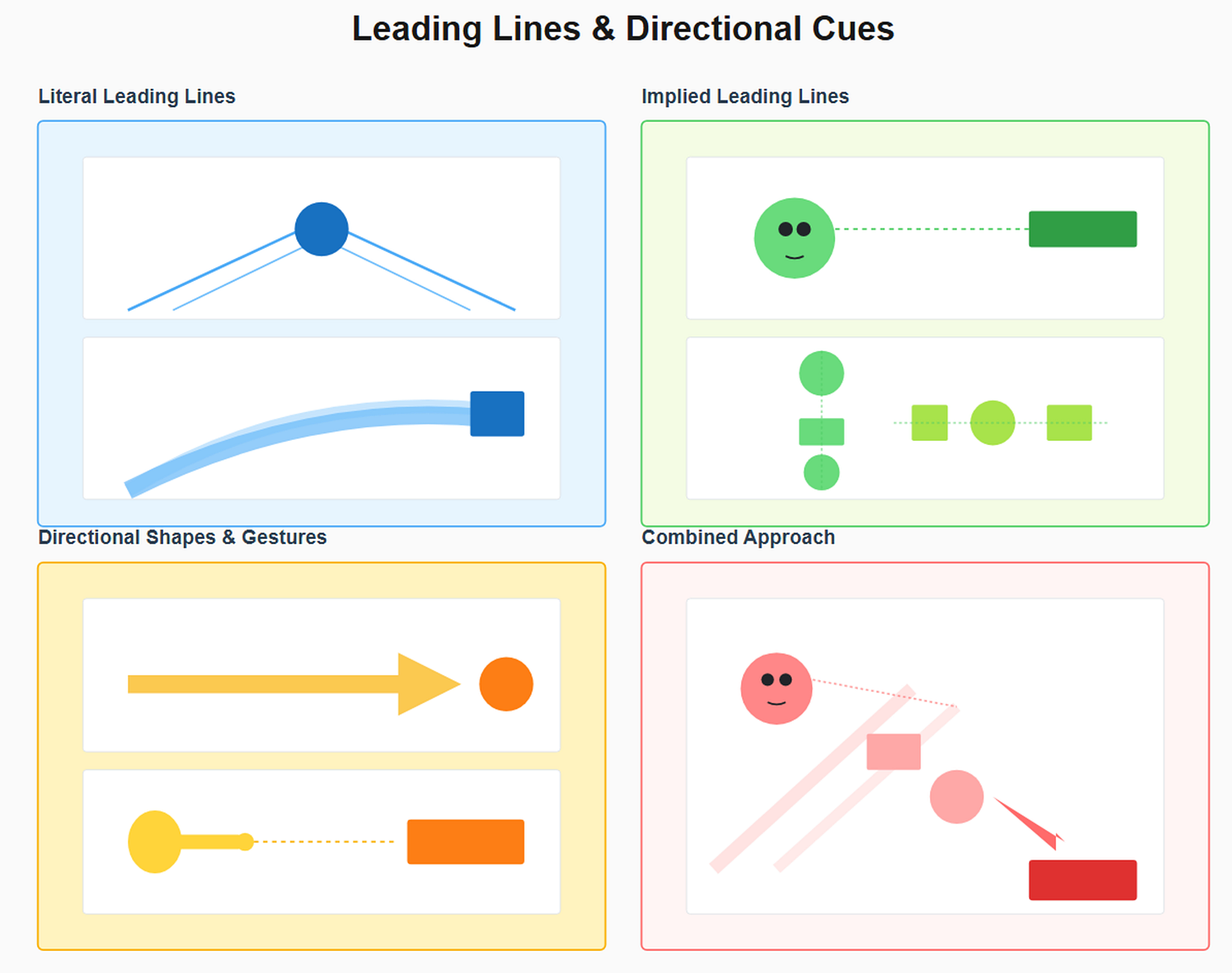

Rule of Thirds

The rule of thirds represents the most widely used compositional guideline in visual arts, from photography to painting to advertising design. This principle divides any rectangular frame into nine equal parts using two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines, creating a grid that resembles a tic-tac-toe board. The four points where these lines intersect become optimal positions for placing key elements, and the lines themselves serve as guides for aligning important features. This simple system has endured because it reliably creates balanced, dynamic compositions that avoid the static feeling of perfectly centered elements while remaining intuitive enough for beginners to apply successfully.

The psychological foundation of the rule of thirds relates to how our eyes process visual information and seek balance. Perfectly centered compositions can feel formal, static, or even monotonous because they lack visual tension. By positioning key elements slightly off-center at the intersection points of the thirds grid, you create a subtle asymmetry that makes the composition more dynamic and interesting while maintaining overall balance. Research into aesthetic preferences consistently shows that people find slightly asymmetrical compositions more engaging than perfectly symmetrical ones, probably because asymmetry creates visual questions that keep the brain engaged: “why is that positioned there?” “what balances that element?” This engagement translates into longer viewing times and better message retention.

In advertising applications, the rule of thirds helps solve common design challenges with elegant simplicity. Positioning a product at one of the four intersection points rather than dead center immediately makes your ad more visually interesting. Aligning your headline along the top horizontal third line creates a strong, stable position that commands attention without dominating the entire space. Placing your call-to-action button at the lower-right intersection point (which coincides with the terminal area of the Z-pattern) positions it exactly where viewers’ eyes naturally finish their scan. For image-based ads, positioning the horizon line along either the top or bottom third rather than the middle creates more dynamic compositions, whether you want to emphasize expansive sky or foreground detail.

The rule of thirds offers a simpler, more practical alternative to the golden ratio for many design situations. While the golden ratio requires precise measurements and calculations (dividing by 1.618), the rule of thirds just needs dividing by three, which any designer can do quickly. For fast-paced environments like social media content creation or responsive design that needs to work across multiple screen sizes, the thirds grid provides a reliable framework that’s easy to implement and adjust. Modern design software often includes rule of thirds overlay options, allowing you to align elements quickly without manual measurement. However, understanding both systems allows you to choose the right tool for each project. The golden ratio might be perfect for a luxury brand’s print campaign where every detail receives meticulous attention, while the rule of thirds might serve better for digital ads that need quick creation and responsive flexibility.

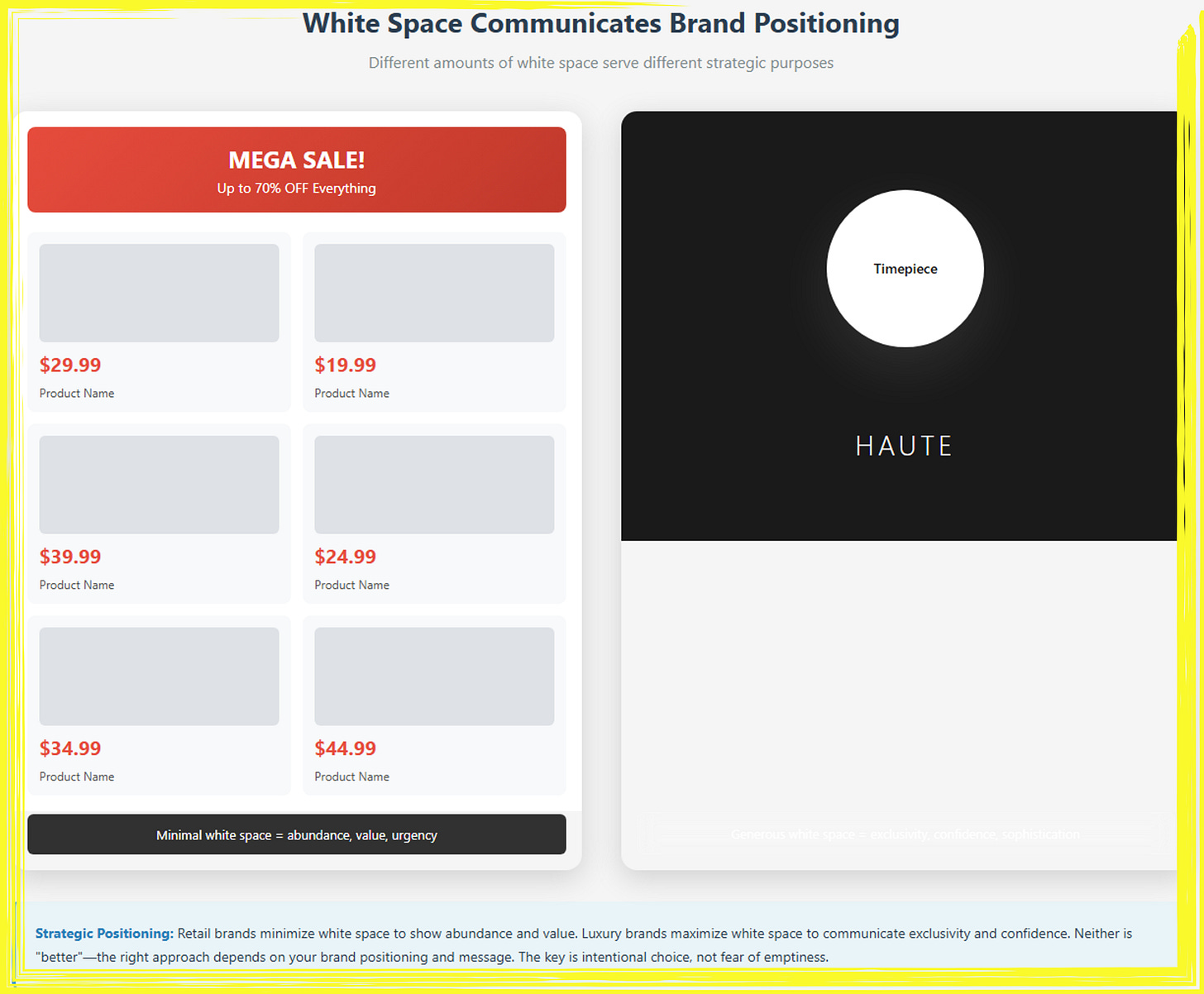

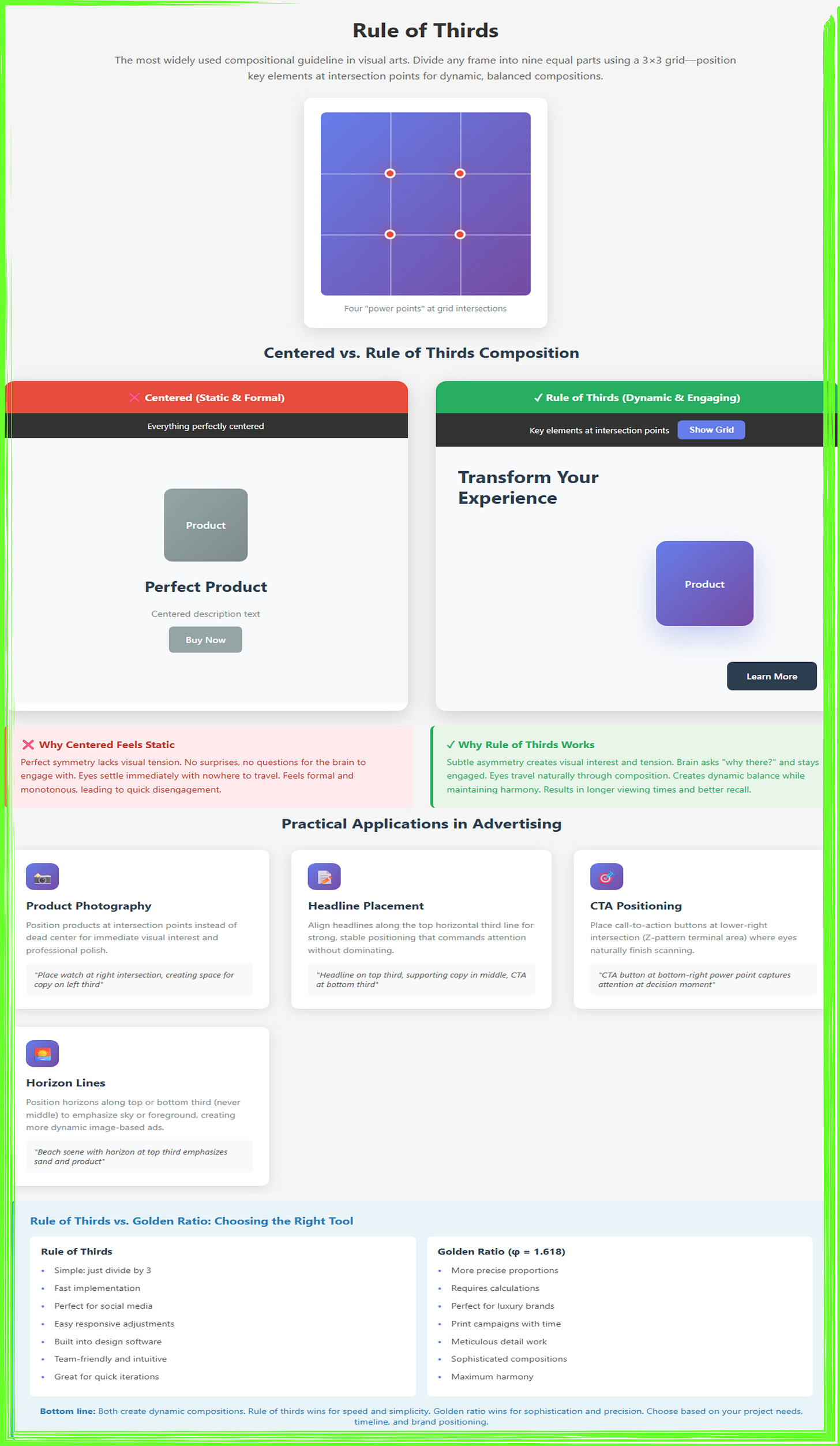

This interactive demonstration illustrates the rule of thirds compositional principle, which divides any frame into nine equal sections using a 3×3 grid. The header shows the basic grid structure with four pulsing red “power points” at line intersections where key elements should be positioned. The side-by-side comparison contrasts a static centered composition (left, using dull grays with all elements on the central axis) against a dynamic rule-of-thirds layout (right, with headline on the top third, product at the upper-right intersection, and CTA at the lower-right terminal point). Color-coded feedback boxes explain why centered compositions feel monotonous while off-center positioning creates engaging visual tension that increases viewing time. Four practical application cards demonstrate optimal positioning for product photography, headlines, CTAs, and horizon lines. The comparison table highlights when to use rule of thirds (simple, fast, ideal for social media and responsive design with built-in software support) versus golden ratio (precise, sophisticated, better for luxury brands and meticulous print campaigns). The interactive grid toggle reveals optimal placement strategies, showing how the rule of thirds provides an intuitive, quickly-implemented alternative to golden ratio calculations while still creating dynamic, balanced compositions that guide viewer attention through intentional asymmetry.

Root 2 Rectangle (√2 ratio - 1:1.414)

The root 2 rectangle, based on the mathematical ratio of 1 to the square root of 2 (approximately 1:1.414), represents one of design’s most practical yet underappreciated proportional systems. This ratio defines the A-series paper sizes used internationally (A4, A3, A2, etc.), which were specifically designed so that folding or cutting the paper in half maintains the same proportions. An A4 sheet is 210mm × 297mm, and when you fold it in half, you get A5 at 148mm × 210mm, the ratio remains constant. This mathematical property makes the root 2 rectangle exceptionally versatile for designs that need to scale across different formats or be printed at various sizes.

The aesthetic appeal of the root 2 rectangle lies in its balance between the golden ratio’s organic elegance and the perfect square’s stability. At 1:1.414, it’s slightly more elongated than a square but less stretched than golden ratio compositions. This makes it feel modern and clean while avoiding the potentially stuffy formality of perfect squares or the sometimes-exaggerated drama of golden ratio layouts. European designers particularly favor this proportion because of its connection to standard paper sizes, meaning designs created with root 2 proportions automatically fit perfectly into common print formats without requiring cropping or awkward scaling that can compromise the composition.

For advertising applications, the root 2 rectangle excels in situations requiring versatility across multiple formats. If you’re designing a campaign that needs to work as magazine ads, posters, flyers, and digital assets, starting with root 2 proportions provides a common framework that scales elegantly. Layout elements positioned according to this ratio maintain their relationships across different sizes, ensuring visual consistency throughout your campaign. This is particularly valuable for brand consistency, when consumers see your ad in a magazine, on a poster, and on their phone screen, the proportional relationships between your logo, headline, and imagery remain constant, reinforcing brand recognition.

Implementing the root 2 system in digital design requires slightly more conscious effort since screen dimensions don’t naturally follow these proportions. However, you can create root 2 containers within your digital layouts, using the ratio to determine the dimensions of key content areas, image crops, or card-based designs. For instance, if you’re designing a grid of product cards, making each card 300 pixels wide and approximately 424 pixels tall (300 × 1.414) creates that pleasing root 2 proportion. You can also use the ratio to determine the relationship between your hero section height and your content width, or between sidebar width and main content width. Like all mathematical systems, root 2 proportions work best when they serve your design goals rather than constraining them, but understanding this ratio adds another valuable tool to your proportional toolkit, particularly for projects with print components or international audiences accustomed to A-series formats.

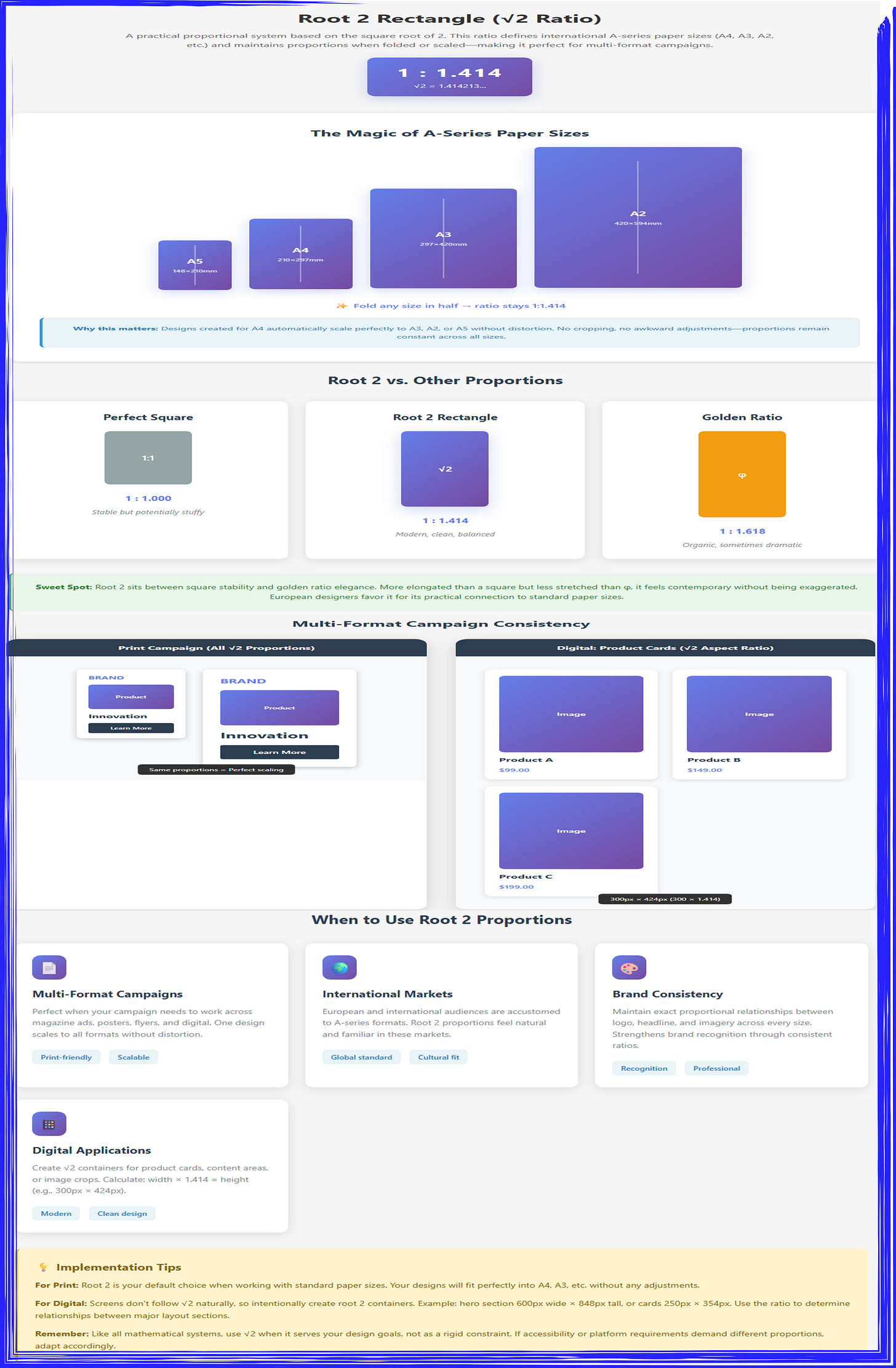

This demonstration illustrates the root 2 proportional system, defined by the ratio 1:1.414, which forms the basis of international A-series paper sizes. The animated paper demo shows A5 through A2 sheets with floating animations and vertical fold indicators, demonstrating the “magic” property where folding any size in half maintains the constant √2 ratio—ensuring designs scale perfectly across formats without distortion or cropping. The ratio comparison visualizes three proportional systems side-by-side: the perfect square (1:1, stable but potentially stuffy in gray), the root 2 rectangle (1:1.414, modern and balanced in purple gradient, positioned as the “sweet spot”), and the golden ratio (1:1.618, organic and dramatic in orange). Multi-format application demos show practical implementation through a print campaign (magazine ad and poster maintaining identical proportional relationships when scaled) and digital product cards (e-commerce grid using 300px × 424px cards calculated as width × 1.414). Four use case cards highlight optimal scenarios: multi-format campaigns (print-friendly and scalable), international markets (global A-series standard with cultural familiarity), brand consistency (maintaining exact proportional relationships across sizes for recognition), and digital applications (creating modern, clean √2 containers for content areas and cards). The implementation tips box provides practical guidance for both print (default choice for standard paper sizes) and digital (intentionally creating root 2 containers like 600px × 848px hero sections), while reminding designers to adapt the system when accessibility or platform requirements demand flexibility rather than treating it as a rigid constraint.

Part 3: Grid Systems & Spacing

The 8-Point Grid System

The 8-point grid system has become the de facto standard in modern interface design, and its principles apply equally well to advertising layouts. This system stipulates that all spacing and sizing should occur in multiples of eight pixels: 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, and so on. While this might seem like an arbitrary constraint, the 8-point system offers profound practical benefits that solve many common design challenges. The number eight was chosen because it’s highly divisible (by 1, 2, 4, and 8), making it easy to create consistent subdivisions and scale designs across different screen densities and resolutions. Modern displays often use pixel density ratios of 2x or 4x, meaning that 8-point measurements scale perfectly without creating fractional pixels that can cause blurry rendering.

The psychological benefits of consistent spacing based on the 8-point grid are substantial. When humans view designs, our brains unconsciously seek patterns and consistency. Random spacing measurements like 7 pixels here, 19 pixels there, and 33 pixels somewhere else create subtle cognitive friction as our pattern-recognition systems fail to find order. Conversely, when all spacing follows a predictable rhythm of 8, 16, 24, 32 pixels, our brains recognize the pattern, and the design feels more organized and professional, even if viewers can’t articulate why. This consistency also speeds up the design process itself, as designers can make spacing decisions quickly without agonizing over whether an element needs 14 or 15 pixels of margin, it simply needs 16 (or 8, or 24).

Implementing an 8-point grid in advertising design starts with establishing your baseline spacing units. Your smallest spacing unit is 8 pixels, used for tight relationships like the gap between an icon and adjacent text, or between related form fields. 16 pixels creates medium separation, useful for spacing between unrelated elements in the same section. 24 or 32 pixels provides clear sectional breaks, signaling to viewers that they’re moving from one content block to another. 40, 48, or larger multiples create major divisions, such as the space between your hero section and your body content. By sticking to these increments, you ensure consistent visual rhythm throughout your design.

The 8-point system also provides a framework for element sizing, not just spacing. Buttons might be 32 or 40 pixels tall, input fields 48 pixels, and icon sizes 16, 24, or 32 pixels. When both the size of elements and the space between them follow the same proportional system, the entire design gains cohesion and feels intentionally crafted rather than arbitrarily assembled. Modern design tools like Figma, Sketch, and Adobe XD support 8-point grids natively, allowing you to snap elements to the grid and maintain consistency automatically. For responsive design, the 8-point system scales beautifully, as you can adjust spacing proportionally across breakpoints (using 16 pixels on mobile where you used 32 pixels on desktop, for example) while maintaining the rhythmic consistency that makes designs feel polished and professional.

This comprehensive infographic explains the 8-point grid system the modern standard for interface design and advertising layouts where all spacing and sizing uses multiples of 8 (8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64...) to create consistent rhythm, scale perfectly across screen densities, and produce organized, professional designs. The top section outlines why 8 works mathematically through four advantages: highly divisible (8 ÷ 2 ÷ 2 ÷ 2 creates easy subdivisions), perfect scaling (aligns cleanly across 1x, 2x, and 3x pixel densities for retina displays), pattern recognition (brain detects consistent rhythms subconsciously), and speed and efficiency (no mental arithmetic required 8×3 simply becomes 24px). A visual divisibility diagram demonstrates how 8 ÷ 1 = 8 boxes, 8 ÷ 2 = 4 boxes, and 8 ÷ 4 = 2 boxes for flexible layout options. The middle comparison contrasts random spacing versus 8-point grid: the left “cognitive friction” panel shows five elements with arbitrary, inconsistent gaps (marked with red X’s) that create visual chaos and require constant deliberation, while the right “consistent rhythm” panel displays the same elements with uniform 8-point spacing (marked with green checks) producing predictable patterns, easier scanning, and professional polish. The 8-Point Spacing Scale section provides practical guidelines: tight spacing (8px) for closely related items like icon-text adjacency, medium separation (16-24px) for distinct but related elements, sectional breaks (24-32px) for major content divisions with labeled examples, and major divisions (40-64px) separating hero sections from body content with comprehensive labeling. The bottom Practical Application demonstrates a complete advertisement using 8-point grids throughout, with a toggle button to show/hide grid lines, displaying proper element spacing (8px), section breaks (24px), and page margins (32px) across both desktop and mobile views proving that mathematical precision creates designs that feel organized, professional, scalable, and effortlessly harmonious.

Safe Zones and Bleed Areas

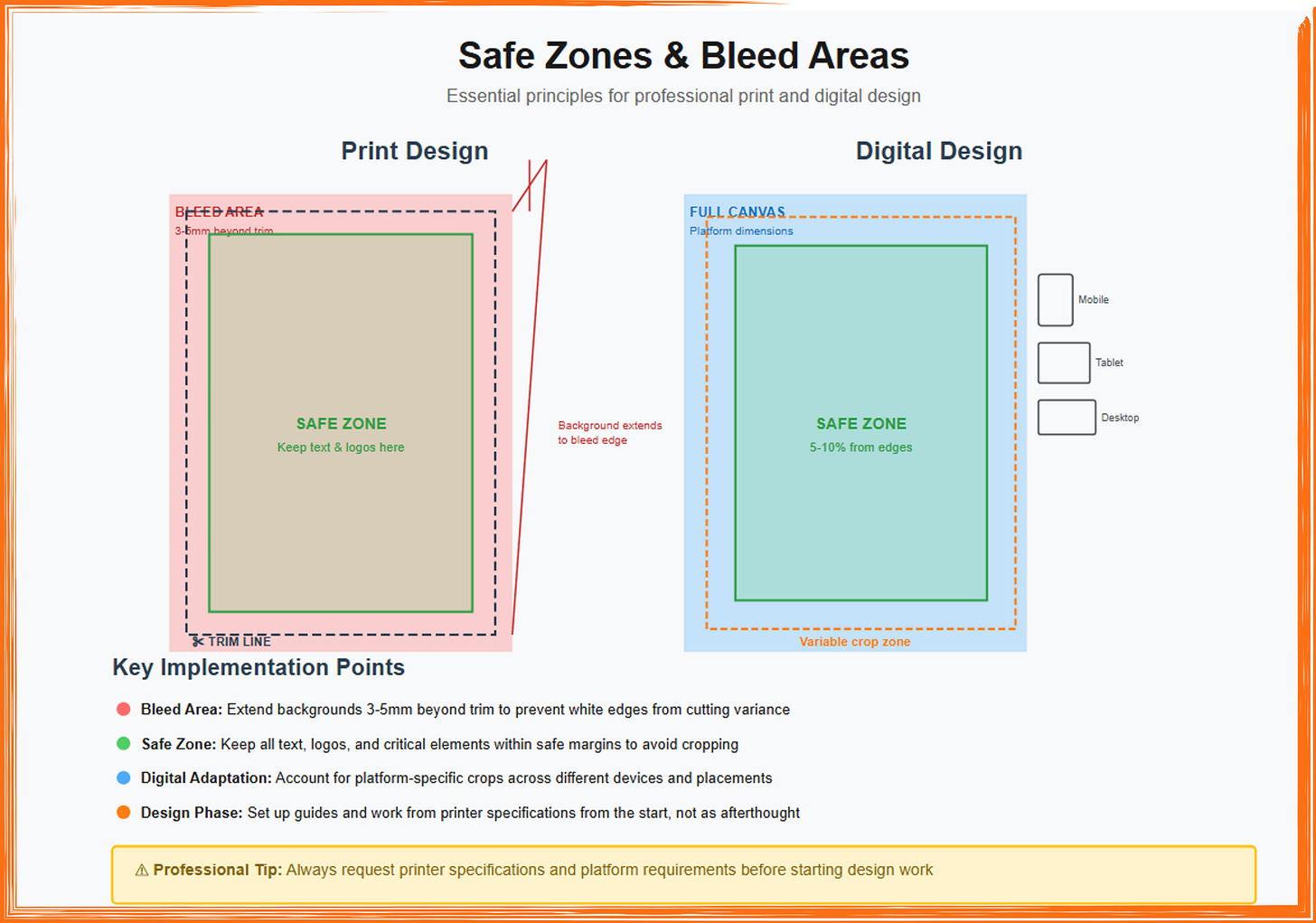

Safe zones and bleed areas represent critical technical concepts that separate amateur designs from professional print-ready advertising. The safe zone is the area where you must keep all essential content, including text, logos, and call-to-action elements, to ensure they won’t be accidentally cropped during printing or display. The bleed area extends beyond the actual trim size of your ad, typically 3-5mm on all sides for print, providing a safety margin so that background colors or images can extend to the edge without risk of white gaps appearing if the cutting is slightly misaligned. Understanding and properly implementing these zones prevents costly reprints and ensures your designs look professional across all media.

The physical realities of printing necessitate these zones. Commercial printing involves large sheets with multiple pieces that get cut apart, and cutting machines, while precise, have tolerances measured in millimeters. If your background color or image stops exactly at the intended edge of your ad, even a tiny misalignment in cutting creates a thin white line where the paper shows through. By extending your background into the bleed area, you guarantee that even with slight cutting variance, your ad will still look intentional and complete. Similarly, if you position text or logos too close to the trim edge, cutting tolerances might clip them, making text harder to read or cutting off part of your logo. The safe zone prevents this by keeping critical elements safely away from dangerous edges.

For digital advertising, safe zone principles remain relevant despite the absence of physical cutting. Different platforms crop images differently depending on device and placement. A Facebook ad might display full-width on desktop but get cropped on mobile devices. Instagram posts appear square in feed but might display in portrait orientation in stories. Email clients render images with varying amounts of the original visible depending on display width and user settings. By keeping your essential content within a safe zone, typically 5-10% away from all edges, you ensure that regardless of how and where your ad displays, the message remains intact and legible. This is particularly crucial for text overlays on images, as partially cropped text can completely change meaning or become unreadable.

Implementing safe zones and bleeds requires planning during the design phase rather than as an afterthought. Start by setting up your document at the correct bleed size, which means your canvas will be larger than the final trim size. In your design software, create guides that show both the trim line (where the piece will be cut) and the safe zone (where important content must stay). Design your backgrounds, patterns, and edge-to-edge images to extend all the way into the bleed area, ensuring continuous coverage. Position all text, logos, buttons, and critical graphics comfortably within the safe zone. Most professional printers provide specific templates showing their required bleed and safe zone measurements, always work from these specifications rather than guessing. For digital work, create your ads at the platform’s specified dimensions, then mentally treat the outer 5-10% as a buffer zone where you avoid placing crucial elements. This disciplined approach ensures your carefully crafted designs survive the transition from screen to final output without unpleasant surprises.

This educational infographic compares safe zones and bleed areas across print and digital advertising design, illustrating essential technical principles that prevent costly production errors. The Print Design panel (left) demonstrates the three-zone system critical for professional print production: the bleed area (red shaded region) extends 3-5mm beyond the final dimensions to prevent white edges from appearing due to cutting variance during the trimming process, the trim line (black dashed border) marks where the printed piece will be physically cut, and the safe zone (green shaded area) indicates where all text, logos, and critical elements must be positioned to avoid accidental cropping with backgrounds intentionally extending to the bleed edge while important content stays within safe margins. The Digital Design panel (right) adapts these concepts for screen-based platforms: the full canvas (blue shaded area with orange dashed border) represents platform-specified dimensions, the variable crop zone (orange dashed boundary) shows where different devices, aspect ratios, and social media placements may crop the image differently across mobile, tablet, and desktop displays, and the safe zone (green shaded area, typically 5-10% from all edges) marks where critical elements should be positioned to ensure visibility across all contexts and avoid platform-specific cropping. The bottom Key Implementation Points section provides four color-coded principles: extend backgrounds into bleed areas (red), keep essential content within safe zones (green), account for platform-specific crops across devices (blue), and establish guides from printer/platform specifications at the project’s start rather than as an afterthought (orange). The yellow warning box emphasizes the professional tip to always request printer specifications and platform requirements before beginning design work, preventing expensive reprints or content loss from improper zone management making this technical knowledge essential for designers creating advertisements destined for both physical printing and digital distribution.

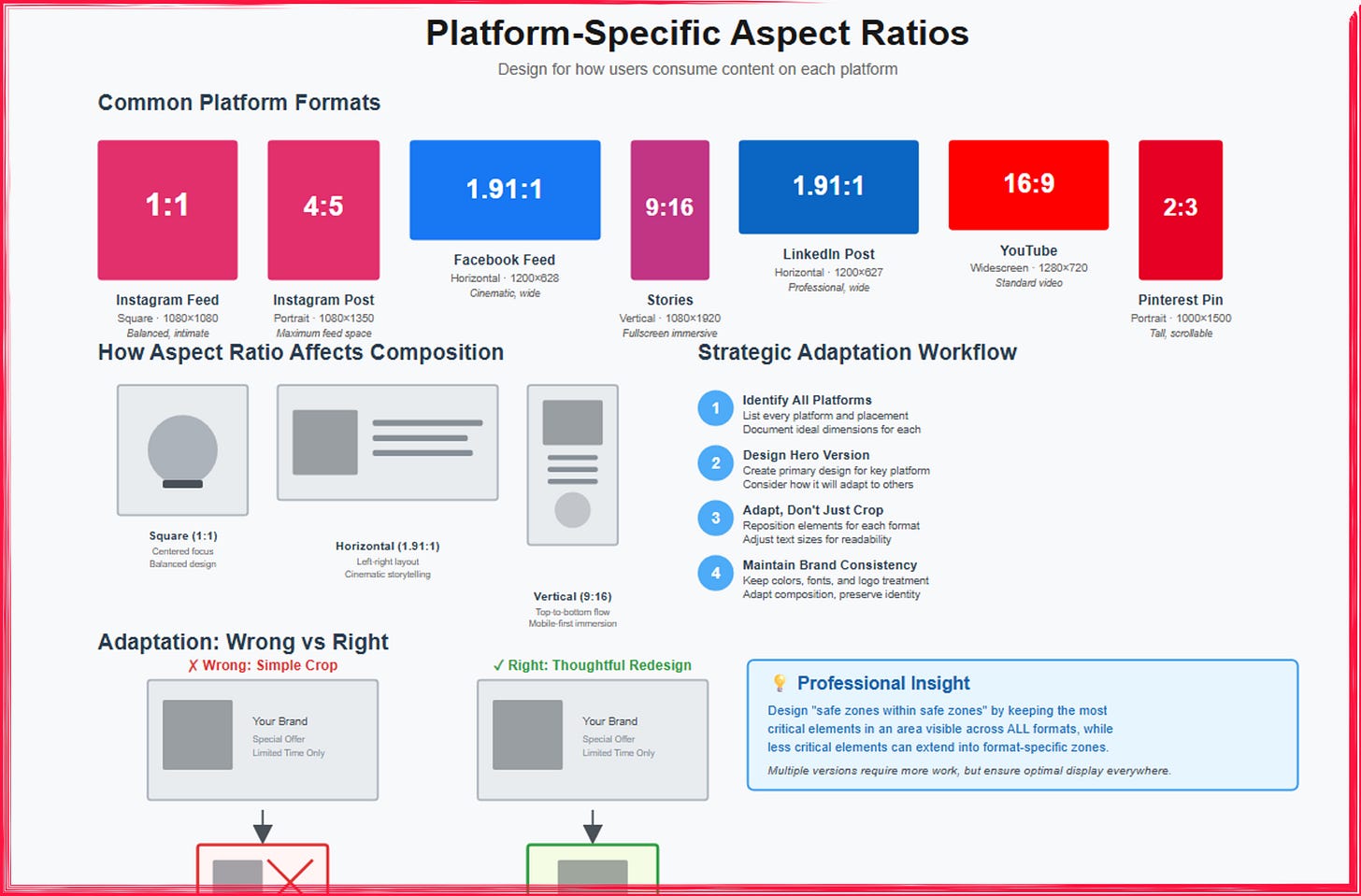

Platform-Specific Aspect Ratios

The fragmented digital landscape means that modern advertisers must design for dozens of different platforms, each with its own preferred image dimensions and aspect ratios. Instagram favors 1:1 squares and 4:5 portraits, Facebook works best with 1.91:1 horizontal formats, Stories demand 9:16 vertical compositions, LinkedIn prefers horizontal images, and display ad networks have their own specifications. Understanding these platform-specific requirements isn’t just about technical compliance, it’s about respecting how users consume content on each platform and ensuring your message displays optimally rather than awkwardly cropped or letterboxed with empty space.

The aspect ratio you choose fundamentally affects your composition and storytelling. A 1:1 square Instagram post creates an intimate, focused feeling, perfect for product photography or simple, centered compositions. The square format forces you to work with roughly equal vertical and horizontal space, which naturally leads to balanced, symmetrical designs or close-cropped imagery. Conversely, a 1.91:1 Facebook horizontal format gives you wide cinematic space, ideal for landscape imagery, group shots, or designs where you want elements arranged left-to-right across the frame. The 9:16 vertical format of Instagram and Facebook Stories creates tall, immersive compositions that fill mobile screens completely, perfect for step-by-step tutorials, before-and-after sequences arranged vertically, or designs that guide eyes from top to bottom.

Designing effectively for multiple platforms requires strategic thinking rather than simply resizing the same composition. The most professional approach involves creating a primary design at your hero platform’s ideal dimensions, then thoughtfully adapting rather than merely cropping for other platforms. This might mean repositioning key elements, adjusting text sizes for readability, or even reconsidering the composition entirely. For instance, if you design a landscape Facebook ad with text positioned on the left and a product image on the right, simply cropping to Instagram’s square format might cut off the text entirely. Instead, you’d want to create a square version where text moves above or below the product, maintaining readability while adapting to the new format.

Systematic workflow processes help manage multi-platform design efficiently. Start by identifying all the platforms and placements where your ad will run, and list the ideal dimensions for each. Design your primary version for your most important platform, keeping in mind how it might adapt to others. Use layers or artboards in your design software to create versions for each platform, maintaining consistent branding elements (colors, fonts, logo treatment) while adjusting composition for each format. Many designers create “safe zones within safe zones,” positioning the most critical elements in an area that will remain visible across all formats, while allowing less critical elements to extend into areas that might be cropped in some versions. Smart asset organization, clear naming conventions, and template systems prevent chaos when managing multiple versions. Remember that while creating multiple versions requires more work upfront, it ensures your message displays optimally everywhere, which dramatically improves campaign performance compared to forcing a single composition across incompatible formats.

This comprehensive infographic educates designers on platform-specific aspect ratios and strategic adaptation workflows for cross-platform advertising campaigns. The Common Platform Formats section displays seven major social media specifications with color-coded rectangles showing actual proportions: Instagram Feed (1:1 square, 1080×1080), Instagram Post (4:5 portrait, 1080×1350), Facebook Feed (1.91:1 horizontal, 1200×628), Stories (9:16 vertical, 1080×1920), LinkedIn Post (1.91:1 horizontal, 1200×627), YouTube (16:9 widescreen, 1280×720), and Pinterest Pin (2:3 portrait, 1000×1500), with each labeled by orientation, dimensions, and use case. The How Aspect Ratio Affects Composition section illustrates three fundamental layout approaches: square format (1:1) favors centered focus and balanced design, horizontal format (1.91:1) enables left-right layout and cinematic storytelling, while vertical format (9:16) follows top-to-bottom flow optimized for mobile-first immersion. The Strategic Adaptation Workflow provides a four-step process using numbered blue circles: (1) identify all platforms and document ideal dimensions, (2) design a hero version for the key platform considering how it will adapt to others, (3) adapt rather than simply crop by repositioning elements for each format and adjusting text sizes for readability, and (4) maintain brand consistency by keeping colors, fonts, and logo treatment consistent while adapting composition to preserve identity. The Adaptation: Wrong vs Right comparison contrasts lazy execution against thoughtful redesign: the wrong approach (marked with red X) shows simple cropping that cuts off critical product imagery when converting from horizontal to square format, while the right approach (marked with green checkmark) demonstrates thoughtful repositioning where the product remains fully visible and text is adjusted for the new dimensions. The Professional Insight box emphasizes the “safe zones within safe zones” strategy—keeping the most critical elements in an area visible across ALL formats while allowing less critical elements to extend into format-specific zones, acknowledging that multiple versions require more work but ensure optimal display everywhere, preventing the common mistake of designing for one platform and discovering critical content gets cropped on others.

Part 4: Color Theory for Advertising

Color Psychology and Emotional Triggers

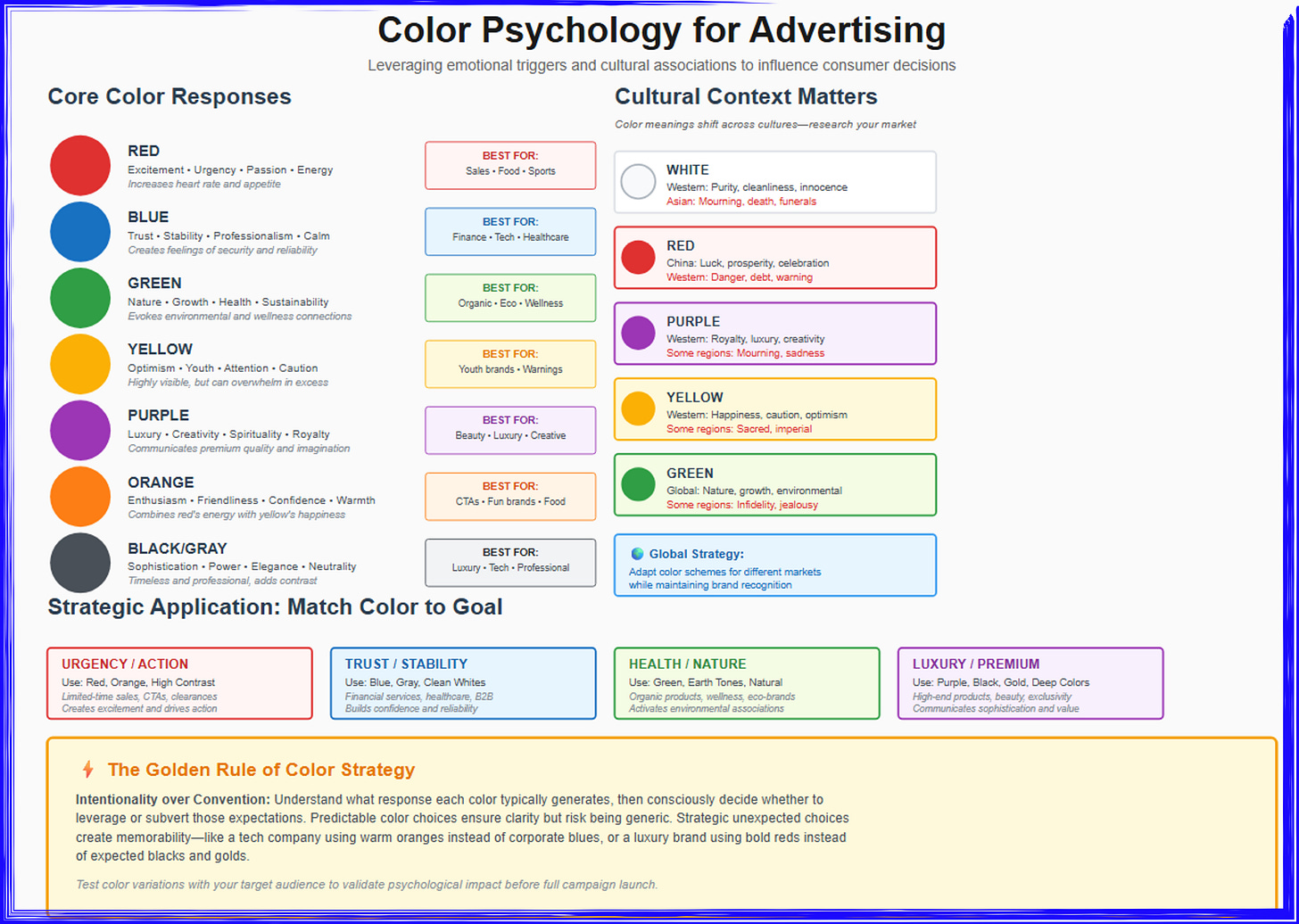

Color operates as one of advertising’s most powerful psychological tools, capable of evoking emotions, triggering memories, and influencing decisions before viewers consciously process your message. This power stems from both biological wiring and cultural conditioning. Humans evolved to respond to color signals in nature, where red fruits against green foliage indicated food sources, blue sky and water suggested resources and safety, while yellow and black patterns warned of dangerous insects. These evolutionary associations persist in modern psychology, with red still triggering arousal and urgency, blue evoking calm and trust, and yellow capturing attention while suggesting caution or optimism depending on context.

Different colors trigger distinctly different psychological responses that smart advertisers leverage strategically. Red increases heart rate and creates feelings of excitement, urgency, passion, and energy, which explains its dominance in clearance sales, sports brands, and food advertising where appetite stimulation matters. Blue generates feelings of trust, stability, professionalism, and calm, making it the color of choice for banks, insurance companies, healthcare providers, and technology companies seeking to communicate reliability. Green connects to nature, growth, health, and sustainability, perfect for organic products, environmental causes, and wellness brands. Yellow radiates optimism, youth, and attention-grabbing brightness, though too much can become overwhelming or suggest caution. Purple communicates luxury, creativity, and spirituality, often appearing in beauty products and premium services.

Cultural context significantly modifies color meanings, requiring research when advertising across different regions. White signifies purity and cleanliness in Western cultures, making it popular for healthcare and wedding-related advertising, but represents mourning and death in many Asian cultures. Red means luck and prosperity in China but can signal danger or debt in Western contexts. Purple suggests royalty and luxury in Western markets but can have negative or mourning-related connotations elsewhere. Understanding these cultural variations prevents embarrassing miscommunications and allows you to leverage positive associations while avoiding negative ones. Global brands often adapt color schemes for different markets, showing the same product in region-appropriate colors or adjusting background treatments while maintaining overall brand recognition.

Applying color psychology effectively requires matching color choices to your specific advertising goals and audience expectations. If you’re promoting a limited-time sale and want to create urgency, red and orange backgrounds with high-contrast elements push viewers toward action. If you’re building trust for a new financial service, blues and grays communicate stability and professionalism. If you’re advertising organic food products, earth tones and greens activate associations with nature and health. However, avoid being so predictable that your ads become generic. Sometimes strategically unexpected color choices create memorability, a tech company using warm, friendly oranges instead of predictable blues, or a luxury brand using bold reds instead of expected blacks and golds. The key is intentionality, understanding what response each color typically generates, then consciously deciding whether to leverage or subvert those expectations based on your strategic goals.

This comprehensive infographic educates advertisers on color psychology principles and strategic color selection for maximum campaign effectiveness. The Core Color Responses section (left) catalogs seven fundamental colors with their psychological triggers and recommended applications: Red (excitement, urgency, passion, energy—increases heart rate and appetite, best for sales, food, and sports), Blue (trust, stability, professionalism, calm—creates feelings of security and reliability, best for finance, tech, and healthcare), Green (nature, growth, health, sustainability—evokes environmental and wellness connections, best for organic, eco, and wellness brands), Yellow (optimism, youth, attention, caution—highly visible but can overwhelm in excess, best for youth brands and warnings), Purple (luxury, creativity, spirituality, royalty—communicates premium quality and imagination, best for beauty, luxury, and creative industries), Orange (enthusiasm, friendliness, confidence, warmth—combines red’s energy with yellow’s happiness, best for CTAs, fun brands, and food), and Black/Gray (sophistication, power, elegance, neutrality—timeless and professional, adds contrast, best for luxury, tech, and professional services). The Cultural Context Matters section (right) warns that color meanings shift dramatically across cultures, providing critical examples: White means purity and cleanliness in Western contexts but represents mourning, death, and funerals in Asian cultures; Red signifies luck, prosperity, and celebration in China but danger, debt, and warning in Western contexts; Purple conveys royalty, luxury, and creativity in the West but mourning and sadness in some regions; Yellow represents happiness, caution, and optimism in the West but is considered sacred and imperial in some regions; Green globally signals nature, growth, and environmental values but indicates infidelity or jealousy in some regions. The Strategic Application: Match Color to Goal section provides four scenario-based recommendations: for Urgency/Action campaigns (limited-time sales, CTAs, clearances), use red, orange, and high contrast to create excitement and drive action; for Trust/Stability messaging (financial services, healthcare, B2B), use blue, gray, and clean whites to build confidence and reliability; for Health/Nature positioning (organic products, wellness, eco-friendly), use green, earth tones, and natural palettes to activate environmental associations; for Luxury/Premium branding (high-end products, beauty, exclusivity), use purple, black, gold, and deep colors to communicate sophistication and value. The bottom Golden Rule of Color Strategy emphasizes intentionality over convention: understand what response each color typically generates, then consciously decide whether to leverage or subvert those expectations—predictable color choices ensure clarity but risk being generic, while strategic unexpected choices create memorability, such as a tech company using warm oranges instead of corporate blues, or a luxury brand using bold reds instead of expected blacks and golds. The final guidance recommends testing color variations with target audiences to validate psychological impact before full campaign launch, ensuring colors resonate appropriately across different cultural contexts and demographic segments.

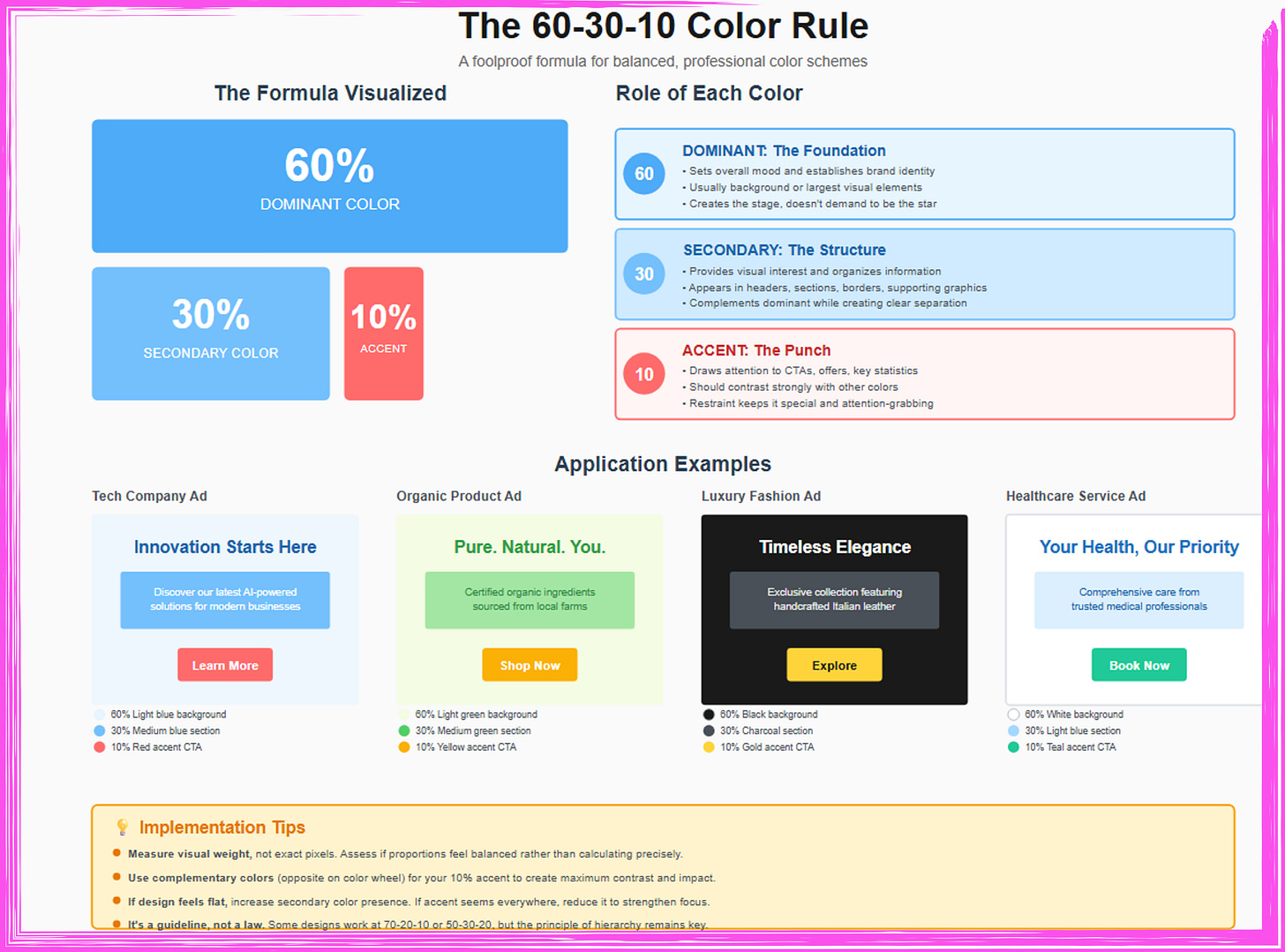

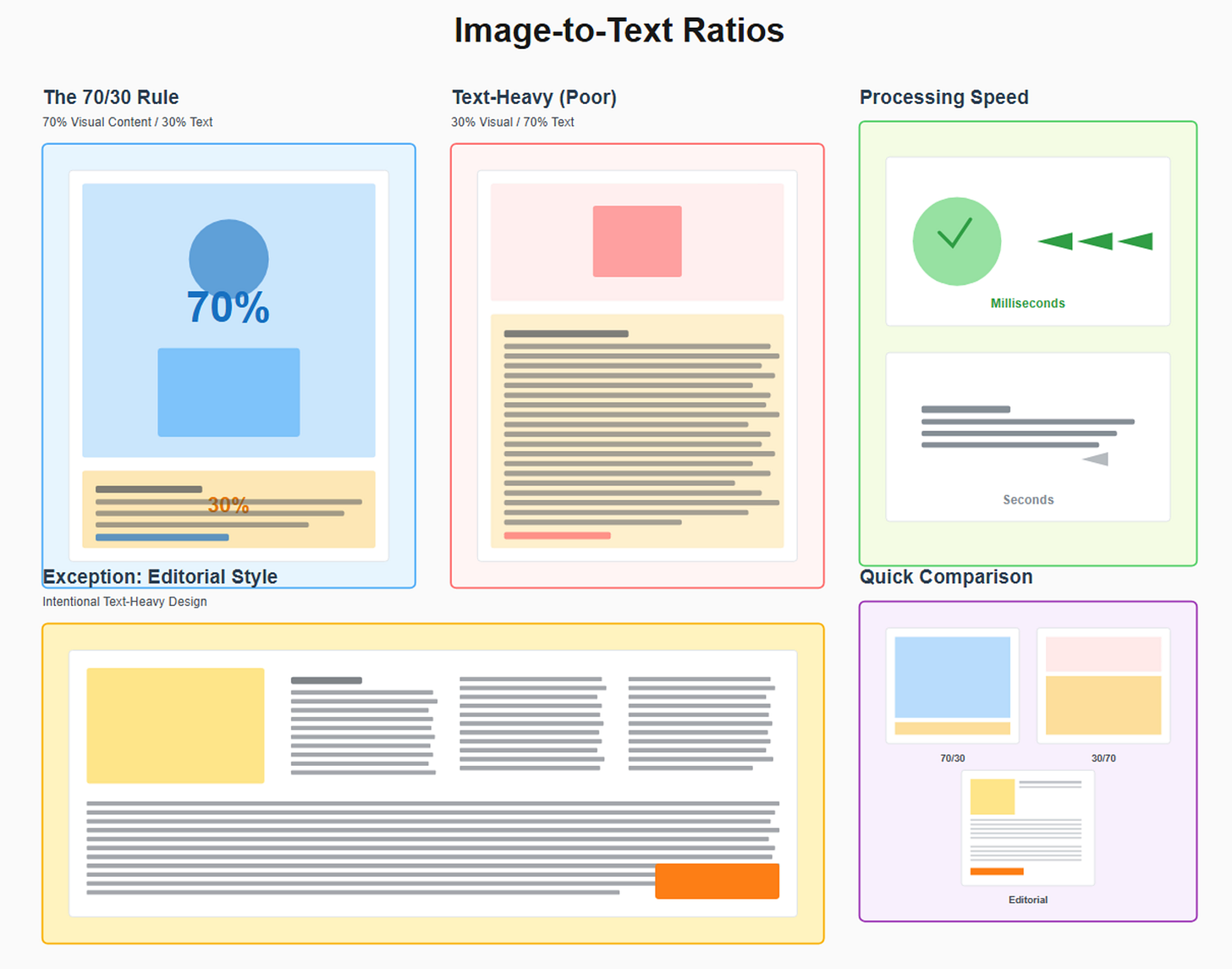

The 60-30-10 Color Rule

The 60-30-10 color rule provides a foolproof formula for creating balanced, professional color schemes that avoid both monotony and chaos. This interior design principle, which translates perfectly to advertising, stipulates that 60% of your design should use a dominant color, 30% should use a secondary supporting color, and 10% should use an accent color for highlights and calls-to-action. This proportion creates visual harmony by establishing clear hierarchy among colors while ensuring enough variety to maintain interest. The formula works because it mirrors how humans naturally process visual information, seeking both pattern recognition (the dominant 60%) and points of interest (the accent 10%) within an organized framework.

The 60% dominant color typically serves as your background or foundational element, establishing the overall mood and connecting to your brand identity. For many ads, this might be white or a light neutral that creates clean, professional space while ensuring text readability. For brands with strong color identities, the dominant color might be their signature hue used as a background wash or in large graphic elements. The key is that this color should support rather than compete with your message, it creates the stage rather than demanding to be the star. This dominant color establishes immediate brand recognition and sets the emotional tone for the entire piece, whether that’s calm and trustworthy (blues), energetic and bold (reds), or natural and organic (greens).

The 30% secondary color provides visual interest and helps organize information without overwhelming the composition. This color often appears in secondary text, supporting graphics, borders, sections, or medium-sized visual elements. It should complement your dominant color while providing enough contrast to create clear visual separation. If your dominant color is a cool blue, your secondary might be a warm gray or a lighter tint of the blue. If you’re using white as your dominant color, your secondary might be your brand’s primary color used for headers, blocks, or shapes. This secondary color creates rhythm and structure, helping viewers parse different sections and understand the relationship between elements without introducing so much variety that the design feels chaotic or unfocused.

The 10% accent color delivers the punch, drawing attention to your most important interactive elements like call-to-action buttons, special offers, or key statistics. This accent should contrast strongly with both your dominant and secondary colors, creating unmistakable focal points that guide viewer actions. Many designers choose complementary colors (opposite on the color wheel) for maximum contrast. If your dominant palette uses blues and grays, your accent might be orange or yellow. If you’re working with greens, a red or pink accent creates drama. The restraint of limiting this bold accent to just 10% of your design ensures it remains special and attention-grabbing rather than becoming overwhelming noise. Every time viewers see that accent color, they should immediately understand “this is important, pay attention here.”

Implementing the 60-30-10 rule requires measuring approximate visual weight rather than exact pixel counts. You don’t need to calculate that precisely 60% of pixels are blue, but rather that blue dominates the overall visual impression. Use your design software’s layer opacity or color fill tools to block out major areas and assess whether the proportions feel balanced. If your accent color seems to be everywhere, reduce it and strengthen your focus. If your design feels flat and monotonous, you might need to increase your secondary color’s presence or make your accent more bold. Like all design rules, 60-30-10 serves as a guideline rather than a rigid law. Some designs might work better at 70-20-10 or 50-30-20, but the principle of establishing clear color hierarchy through proportional allocation remains universally valuable for creating cohesive, professional advertising that guides viewers effectively.

This infographic presents the 60-30-10 color rule a foolproof formula for creating balanced, professional color schemes in advertising design. The Formula Visualized section (top left) displays the proportional relationship through scaled rectangles: a large blue block representing 60% dominant color, a medium blue block showing 30% secondary color, and a small coral block indicating 10% accent color, making the hierarchy immediately clear through size differentiation. The Role of Each Color section (top right) explains the strategic function of each proportion: the 60% Dominant color (blue circle) serves as the foundation that sets overall mood and establishes brand identity, typically appearing as backgrounds or largest visual elements, creating the stage without demanding to be the star; the 30% Secondary color (lighter blue circle) provides visual interest and organizes information, appearing in headers, sections, borders, and supporting graphics, complementing the dominant color while creating clear separation and structure; the 10% Accent color (coral circle) delivers the punch by drawing attention to CTAs, offers, and key statistics, contrasting strongly with other colors while maintaining restraint to preserve its attention-grabbing power and special status. The Application Examples section demonstrates four real-world implementations: Tech Company Ad uses 60% light blue background (trust, innovation), 30% medium blue section (structured information), and 10% red accent CTA button (urgency); Organic Product Ad employs 60% light green background (natural, eco-friendly), 30% medium green section (health focus), and 10% yellow accent CTA (optimism, action); Luxury Fashion Ad leverages 60% black background (sophistication, elegance), 30% charcoal section (premium quality), and 10% gold accent CTA (luxury, exclusivity); Healthcare Service Ad utilizes 60% white background (cleanliness, trust), 30% light blue section (calm, professionalism), and 10% teal accent CTA (wellness, action). The Implementation Tips box (bottom) provides practical guidance with four key points: measure visual weight rather than exact pixels by assessing if proportions feel balanced rather than calculating precisely; use complementary colors (opposite on the color wheel) for the 10% accent to create maximum contrast and impact; if design feels flat, increase secondary color presence, or if accent seems everywhere, reduce it to strengthen focus; and emphasizes that it’s a guideline, not a law some designs work at 70-20-10 or 50-30-20, but the principle of establishing clear visual hierarchy through proportional color distribution remains key to preventing chaotic, unprofessional color schemes where every element competes equally for attention.

Contrast for Readability and Attention

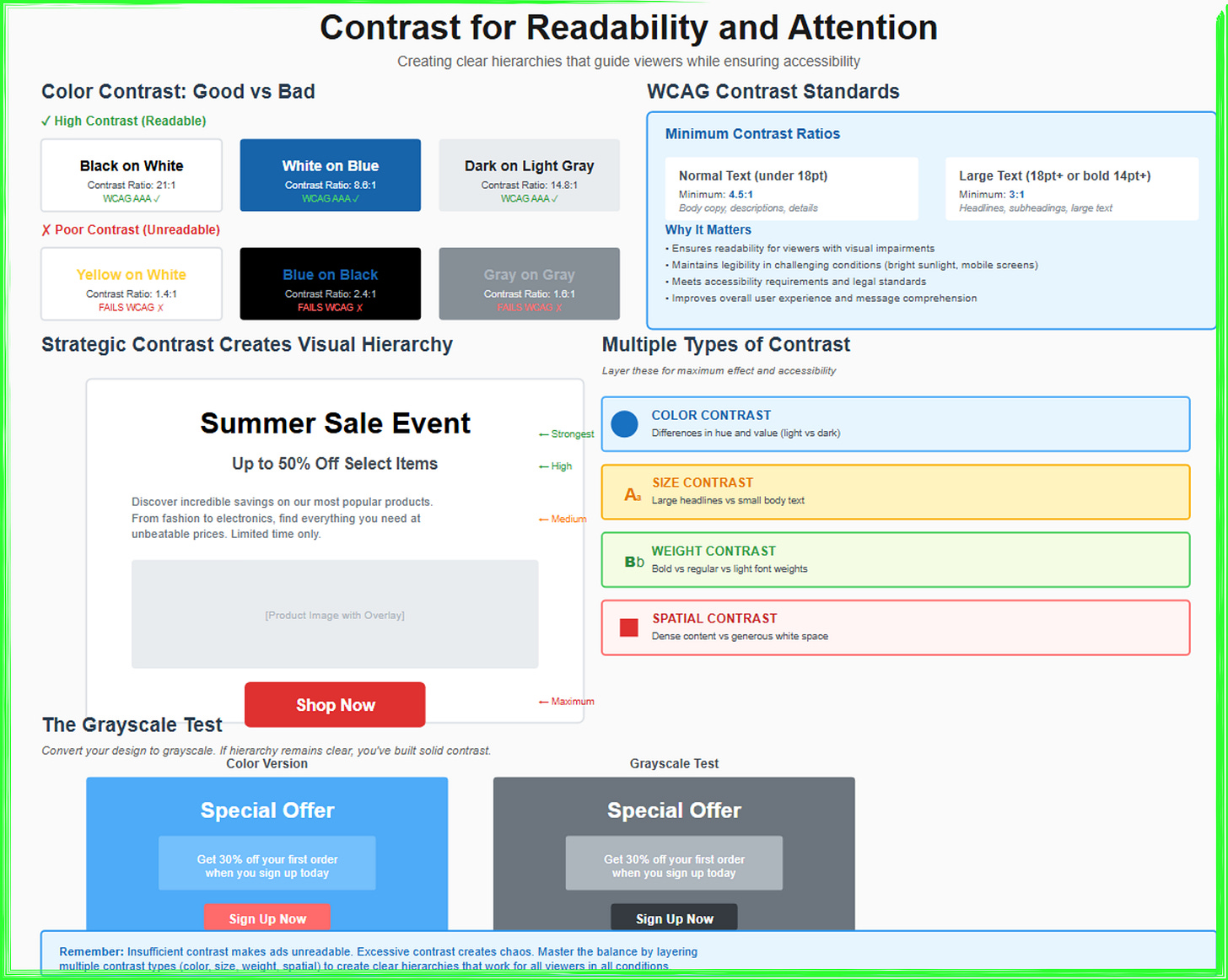

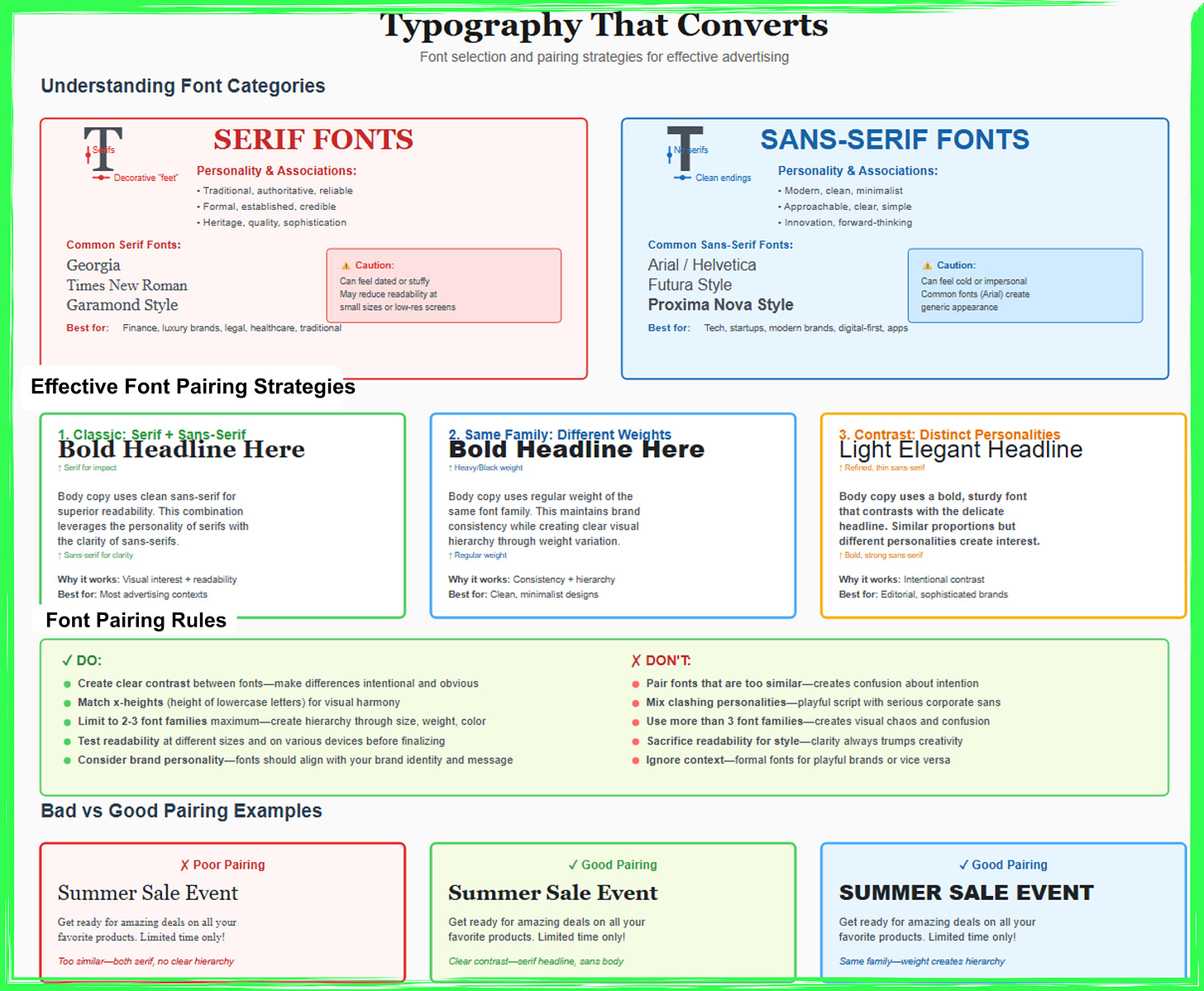

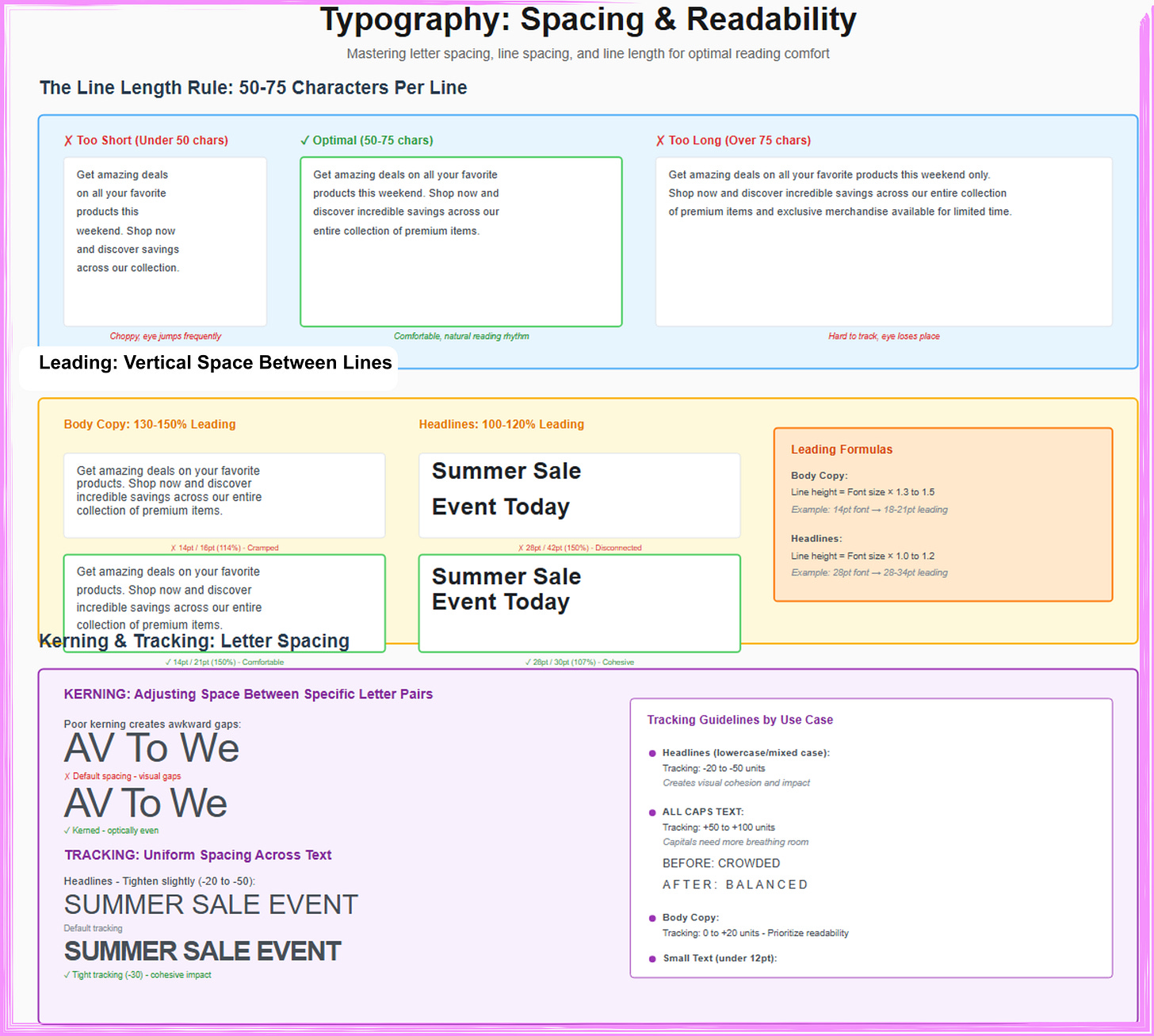

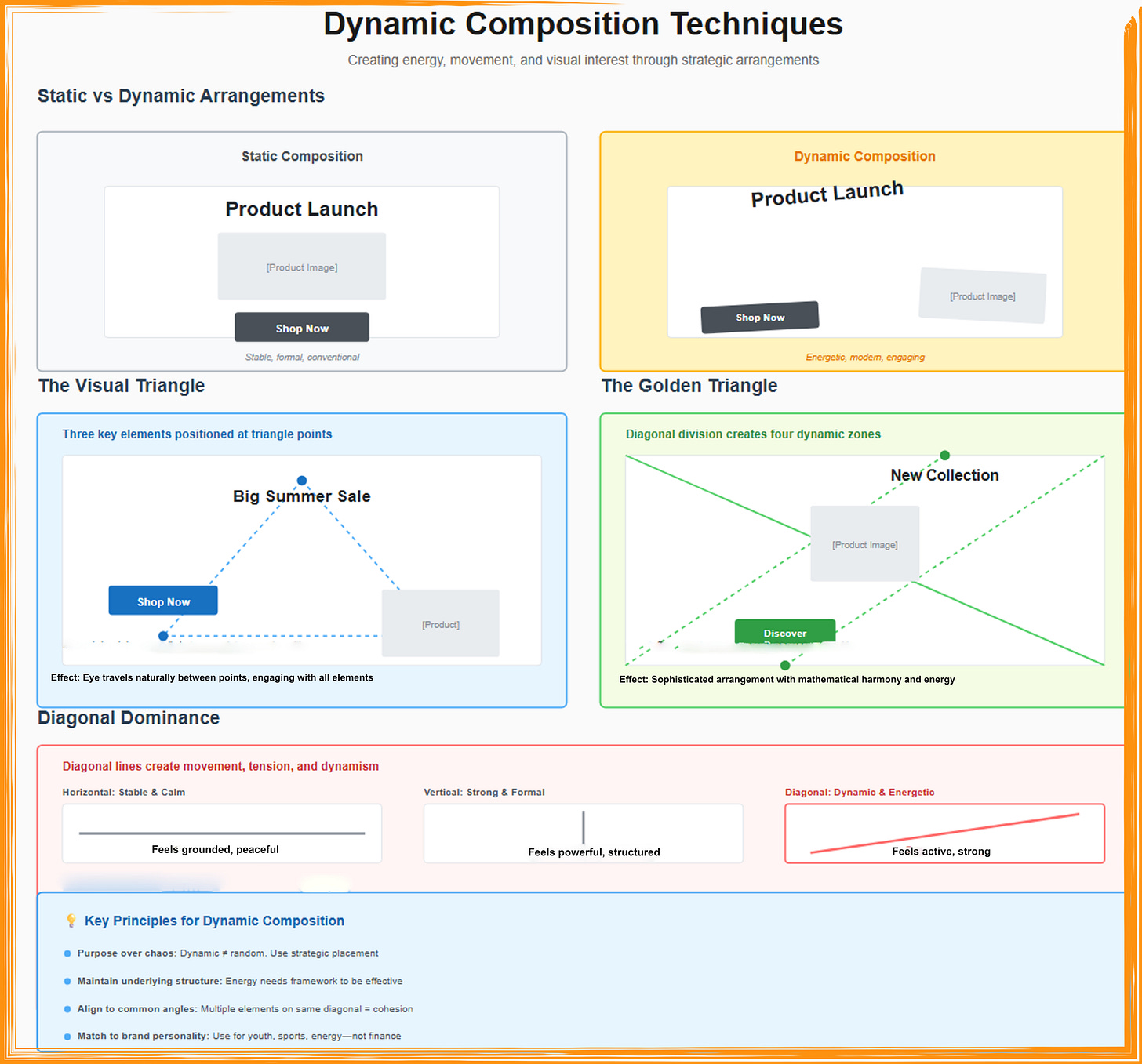

Contrast represents the difference in visual properties that makes an element distinguishable from its surroundings, and it’s perhaps the single most important factor determining whether your ad gets read or ignored. Insufficient contrast makes text difficult or impossible to read, forcing viewers to strain or simply move on to easier content. Excessive or improperly used contrast creates visual chaos where everything screams for attention and nothing receives it. Mastering contrast means understanding how to use differences in color, value, size, shape, and texture to create clear hierarchies that guide viewers effortlessly through your message while ensuring every element remains accessible and legible.

Color contrast, the most obvious form, relies on the difference between hue and value (lightness/darkness). Light text on dark backgrounds or dark text on light backgrounds creates the fundamental contrast needed for legibility. However, not all color combinations work equally well. Yellow text on white backgrounds fails despite being different hues because they have similar values, they’re both light. Similarly, dark blue text on black backgrounds struggles because both values are dark. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) specify minimum contrast ratios: 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text (18pt or larger). Tools like contrast checkers help verify your color combinations meet these standards, ensuring your ads remain readable for viewers with visual impairments or viewing in challenging conditions like bright sunlight on mobile screens.

Beyond simple legibility, strategic contrast creates visual hierarchy and guides attention. Your headline should have stronger contrast against the background than your body copy, making it more prominent and ensuring viewers see your main message first. Call-to-action buttons need maximum contrast to stand out as interactive elements distinct from passive content. This might mean using a bright accent color against a neutral background, or ensuring buttons have clear borders and shadows that separate them from surrounding elements. Similarly, hero images should contrast with text overlays, sometimes requiring semi-transparent gradient overlays that darken or lighten portions of images to ensure text remains readable regardless of the underlying imagery.

Size, weight, and spatial contrast work alongside color contrast to create comprehensive visual hierarchies. A large, bold headline creates contrast with smaller, regular-weight body text not through color but through scale and weight. Tight letter spacing in headlines contrasts with generous line spacing in body copy. Dense sections of content contrast with generous white space. These non-color contrasts prove especially important for accessible design, as they ensure hierarchy remains clear even for viewers with color blindness. The most effective ads layer multiple types of contrast: size, weight, color, and spatial contrast all working together to create unmistakable hierarchies. Test your designs by converting them to grayscale if the hierarchy still works without color, you’ve built solid contrast structure. If elements become indistinguishable in grayscale, you’re relying too heavily on color alone and need to strengthen other contrast types to ensure accessibility and clarity across all viewing conditions.